| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 29/10/2025 x |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Paperfolding of Isao Honda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Introduction

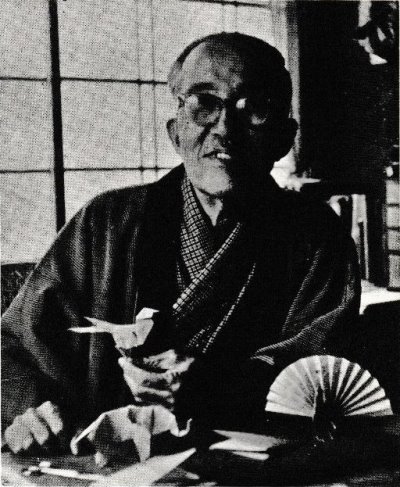

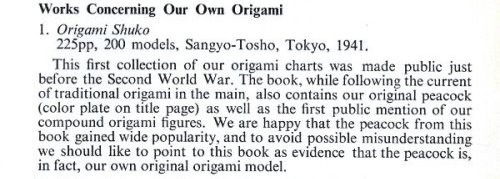

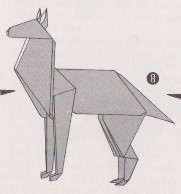

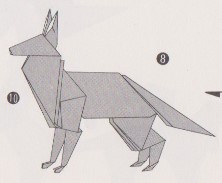

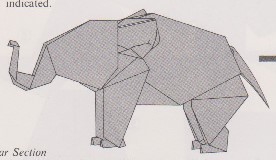

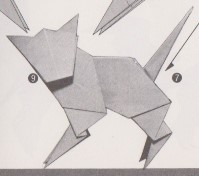

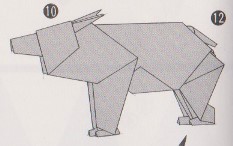

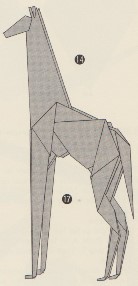

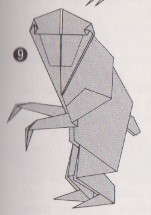

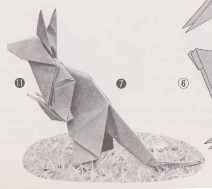

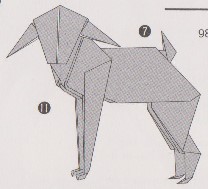

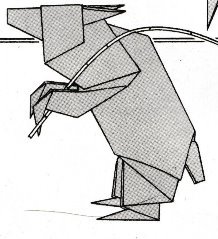

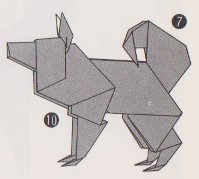

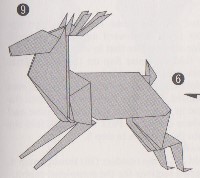

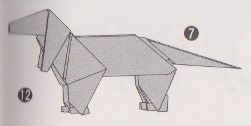

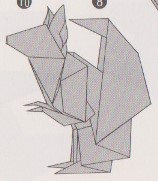

Isao Honda was born in 1888 and died in 1976. He published several important books on origami in Japanese during the first half of the 20th century and many others in English from 1957 onwards, which, along with those written by Florence Sakade, were influential in introducing Japanese-style paperfolding to Europe and the Americas, and in creating the belief that recreational paperfolding, or origami as he called it, was a specifically Japanese form of art. It is clear from his books that Honda had no idea that many traditional Japanese designs had originated as Western paperfolds. His books contained a mixture of traditional paperfolds, Honda's own original designs, and designs by Akira Yoshizawa. However, Honda does not usually say which are which, and it is often difficult to know into which category some of the folds should be placed. Honda frequently used designs in more than one publication, indeed, this frequent re-use of designs is almost his trademark. Honda also published books on other subjects which are not listed on this page. ********** Honda's original designs Honda considered origami to be a living tradition, in which, in each era, the designs of the past were respected while new designs were added. In 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' he wrote, roughly translated: 'Origami ... this "paper craft game" has been passed down in a relay-like manner from mothers to children throughout the centuries of Japan's past, with new works reflecting each era being added along the way, and it can be said to be one of the cultural heritages unparalleled in the world. Rather than leaving this precious tradition as a classical relic, passing it on, while also developing it in new ways, can be said to be one of the duties that our ancestors have imposed on us.' *** Single-sheet and multiple sheet designs In 'All About Origami' (see entry for 1960 below) Honda specifically claimed that he designed 'A Dragonfly of 'Kanomado'' and 'A Baby Turtle', both of which are developed from hexagons without the use of cuts. It is quite possible, indeed probable, that many of the other single-sheet and multiple-sheet designs that first appear, and regularly appear, in Honda's books are also his original designs, but since he does not make any specific claims about them we cannot be sure, for any individual design, whether or not this is the case. Some could simply be pre-existing designs which he has collected and reproduced. Links to full information about many (thougfh not all) of those single-sheet and multiple-sheet designs which are quite possibly his original workare given in the table below. *** Compound Designs There are several places in Honda's book 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below) where Honda claims to have originated the idea of folding compound figures, particularly those made by glueing two bird bases, or equivalent forms made from other paper shapes, together. He also specifically claims that certain compound designs, the peacock, horse, cat, monkey etc from two squares, the eagle and the dragon from two equilateral triangles, and the giraffe, alligator and three monkeys from two rhombuses, are his own original inventions. The 'etc' presumably means that Honda is claiming to be the designer of the other compound figures listed on page 130 as well. (from the biographical notes on the book jacket)

From the Bibliographical Note p261

From p252

Similarly, the dust jacket of 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' (from 1969), states, roughly translated: 'Honda respected the true essence of origami, which has developed in close contact with the hearts of Japanese people and always maintained a close and orthodox teaching philosophy. He promoted the synthesis of origami traditions and their development, and came up with compound origami, which expanded the possibilities of origami several fold. Many people mistakenly believe that animal creations made with compound origami have existed for a long time, but this is also proof that this revolutionary development is rooted in tradition.' The table below records where and when each of Isao Honda's compound designs first appeared. The early compound designs become more sophisticated over time. Some of the designs also appear in several variations (which are not recorded in this table, and many of which are very similar to each other). Most of these designs do not have their own dedicated page. In 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' Isao Honda wrote, roughly translated: 'I would like to state that the first works based on this concept (ie making a compound design from two folded sheets) were the 'Peacock' and 'Horse' published in the 1941 issue of 'Origami Handicraft'.

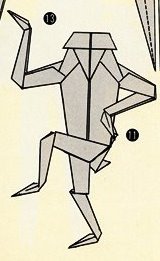

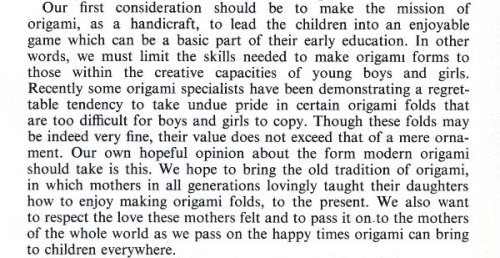

********** Honda's view of the nature of origami Honda believed that origami designs should be fundamentally simple and that they should be composed of straight line folds. He also believed that origami designs should be easily reproducible, especially by children. This, from 'The World of Origami' (from 1965).

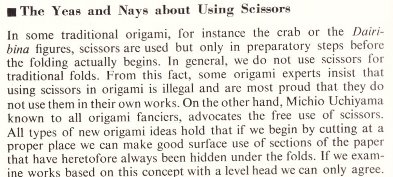

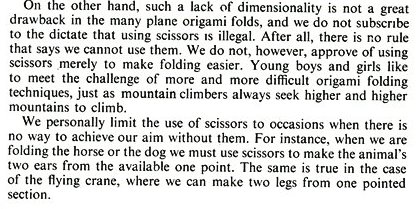

Similar views were also stated in 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' (from 1969), where he wrote, roughly translated: 'Due to the rapid Westernisation that began in the Meiji period, many Japanese traditions are now in danger, and origami is no exception, in the sense that its legitimacy is being lost. In an effort to be unnecessarily unusual and with too much emphasis on artistic value, origami's original appeal as something familiar, easy for anyone to fold, and easy to put together into simple concise shapes, is being lost.' This belief may well be at the core of the deterioration of his relationship with Yoshizawa (see below). ********** Honda's paperfolding ethics As well as being happy to develop designs from more than one sheet of paper, Honda was also happy to make use of cuts, particularly to add detail to the design to increase verisimilitude, for instance, to turn single legs, ears etc into two, but also on some occasions to free paper from inside a design in order to broaden the proportions of a body. He is also willing, on occasion, to use decoration or pre-decorated paper. At several points in 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below), Honda discusses the ethics of using cuts. The chapter on 'The Ideal Modern Origami' includes a section on 'The Yeas and Nays about Using Scissors'. in which he says:

The passage 'some origami experts insist that using scissors in origami is illegal and are most proud that they do not use them in their own works' is probably a reference to Yoshizawa. But just before this he says:

In his discussion of the merits of Uchiyama's crab, Honda says:

*** In the bibliography, Honda lists Michio Uchiyama's 'Sosaku Origami' and also takes the opportunity to again comment on his frequent use of cuts.

********** Honda's relationship with Akira Yoshizawa Honda and Yoshizawa had a complex relationship which appears to have been good at first, but which deteriorated over the years for reasons that we do not completely understand. Honda was, of course, a much older man. Honda included several of Yoshizawa's designs in his book 'Origami Shuko' (see entry for 1944 below). Honda mentions Yoshizawa several times in the book. He says that many of the pieces by Yoshizawa use the revolutionary technique of folding from a triangle, and since many of their themes cannot be produced with any degree of realism from squares of paper, he is grateful to Yoshizawa for his valuable research and the improvement his models have brought to the book. He also says that the Hen, Rooster and Chicks shown at the front of the book require a level of technique almost impossible to diagram. Yoshizawa's decorated helmet, the tea kettle, the ogre mask, the raccoon-dog stomach drum, and so on, have both a traditional flavour and a very original technique, so his work should be highly praised, but the Hen, Rooster and Chicks are far too complicated for the kind of handicraft education for young people intended by this book, and so they have been left out. (Note that of the designs mentioned here, only the raccoon-dog stomach drum (design 57) is in fact diagrammed in the book.) Where Honda included designs he had attributed to Yoshizawa in 'Origami Shuko' in his later books he did not always repeat the attribution there. According to the book jacket of 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below) Akira Yoshizawa had been Honda's pupil.

In the same volume, Honda promotes Yoshizawa's book 'Origami Dokuhon', but also, on several occasions, denigrates Yoshizawa's creative work: From p292

There are also passages in the book where, although Yoshizawa is not specifically named, he seems to be the intended target of Honda's invective:

********** Honda's view of paperfolding history In his author's introduction to 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' Honda says, roughly translated: 'Origami ... this "paper craft game" has been passed down in a relay-like manner from mothers to children throughout the centuries of Japan's past, with new works reflecting each era being added along the way, and it can be said to be one of the cultural heritages unparalleled in the world. Rather than leaving this precious tradition as a classical relic, passing it on, while also developing it in new ways, can be said to be one of the duties that our ancestors have imposed on us.' In 'The World of Origami' Honda advances the view that the creation of the Paper Crane was 'accidental'.

Honda believes that origami and the making of kimono were closely linked and that both declined together:

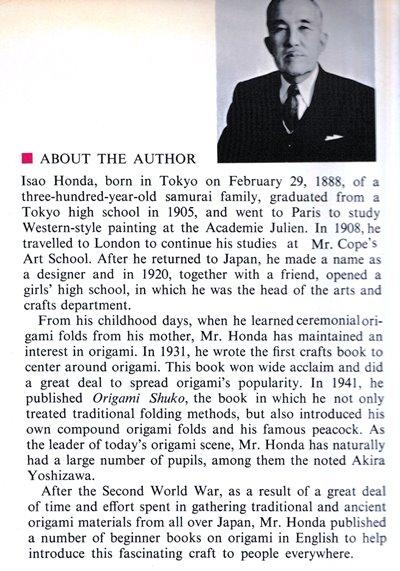

Honda believed that by the early 1930s the practice of traditional style origami had gone into serious decline and set out to revers this trend. ********** Chronology Apart from his books, and their book jackets, I do not know of any primary sources relating to his life. This page has therefore mainly been constructed from secondary sources. I have, however, cross-referenced these to statements made in his books wherever possible. A list of the main secondary sources relied on can be found at the foot of this page. They are referenced within the Chronology in brackets as (DL1) etc. Words in italics are direct quotations from secondary sources. 1888 According to the book jacket of 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below), Honda was born in Tokyo on 29th February 1888 of a 'three-hundred-year-old samurai family'. 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' contains the information that the Honda family were 'a vassal of the Togukawa shoganate'. The book jacket of 'All About Origami' (see entry for 1960 below) gives his year of birth as 1885, but this is probably an error. The Foreword in the same book states he was born in 1888 and goes on to describe how he learned origami at school and from his mother as a child.

********** 1905 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' contains the information that 'After graduating from Tokyo High School in 1905 he went abroad to study Western painting. and studied under Umehara Ryuzaburo, Yasui Taro and Arishima Ikuma at the Academie Julian. ********** 1907 Of this period in his life Honda writes in the Foreword to 'All About Origami' (see entry for 1960 below):

Reference here to origami as 'The Finest Hand Art in the World' is probably to paperfolding as a means of promoting manual dexterity in children within the French educational system. 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' states that 'By chance he demonstrated origami to some French people, using a napkin, who were amazed, and he became fascinated with the pursuit of this Japanese tradition.' ********** 1908 According to the book jacket of 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below), Honda 'travelled to London to continue his studies at Mr Cope's Art School'. According to DL1 'At the end of his four years in France and England, Honda toured other European countries and returned home by way of China.' ********** 1920 According to the book jacket of 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below), 'After he returned to Japan he made a name as a designer and in 1920, together with a friend, opened a girl's high school in which he was head of the arts and crafts department'. 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' states that 'In 1920 he founded a girl's school and became head of the art department.' ********** 1931 Publication of his book 'Origami Part 1' (upper) (in Japanese) 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' states that 'In 1931 he published a book on Japanese crafts, focussing on origami. This was the first book to be published since the Meiji era, and it led to the rapid spread of origami, with origami being incorporated into early childhood education throughout the country.' It should be noted that this statement is untrue. Many books containing information about the use of paperfolding as a handicraft in schools were published in Japan between 1912 and 1931 (See Sources page for details). ********** 1932 Publication of his book 'Origami Part 2' (lower) (in Japanese) Publication of his book 'Golden Bat Cigarette Packet Handicrafts'. ********** 1935 Publication of his book Kirigami (in Japanese) ********** 1941 Publication of Hondais compound 'Peacock' and 'Horse' designs in the 1941 issue of 'Origami Handicraft'. ********** 1944 Publication of his book 'Origami Shuko' (in Japanese). According to the book jacket of 'The World of Origami' (see entry for 1965 below) this book was published in 1941, but this is an error. This book contains diagrams for several compound designs, including Honda's Peacock. There is no claim of authorship of these designs in the book but Honda later claimed that he originated the technique and that, apart from the compound camel, which is attributed to Yoshizawa, the compound designs in this book were his own. (See entry for 1965 below). ********** 1957 Publication of his book 'Origami: Japanese Paper Folding' (in English) (DL2). Note that this book was reissued in the same year as 'Origami: Japanese Paperfolding - Penguin Book'. ********** 1958 Publication of his book 'Origami: Japanese Paper Folding: Monkey Book' (in English) ********** 1959 Publication of his book 'How to Make Origami' (in English) Publication of his book 'Origami: Japanese Paper Folding: Fuji Book' (in English) Publication of his book 'Origami: Japanese Paper Folding: Sakura Book' (in English) ********** 1960 Publication of his book 'All About Origami' (in English) Publication of his book 'Pocket Guide to Origami: Bow-Wow Book' (in English) Publication of his book 'Pocket Guide to Origami: Bow-Wow Book' (in English) ********** 1961 Publication of his book 'Origami Zoo: Bird Book' (in English) Publication of his book 'Origami Zoo: Animal Book' (in English) ********** 1962 Publication of his books 'Living Origami Book 1' and 'Living Origami Book 2' (in English) ********** 1964 Publication of his book 'Noshi - Classic Origami in Japan' (in English) ********** A series of 3 books titled 'My Origami: Birds / Flowers / Animals and Fishes were produced by Zokeisha Publications of Tokyo and published by Crown Publishers Inc, in New York in 1964. Of them, David Lister says: 'At the time of publication there was some discussion in “The Origamian” as to whether the books were by Yoshizawa or Honda. They were definitely not by Yoshizawa. Many of the models are traditional, but some of the birds in “My Origami Birds” are the same as those in books by Isao Honda and they may be his work used without his permisssion.' Versions of these three books were also published in other countries and languages. There is no proof, however, that Honda did write these books and they may have used material from his earlier works withoiut permission. ********** 1965 Publication of his book 'The World of Origami' (in English). Some useful biographical information about Isao Honda was printed on the inside rear flap of the book jacket.

********** Honda knew about Gershon Legman's 'Bibliography of Paperfolding', published in 1952, when he wrote this book

********** 1967 Publication of his book 'Origami Holiday' (in English) Publication of his book 'Origami Festival' (in English). Publication of his book 'Origami Folding Fun: Kangaroo Book' (in English)) Publication of his book 'Origami Folding Fun: Pony Book' (in English) ********** 1969 Publication of his book 'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' (Heart of Japan, Traditional Origami) (in Japanese) David Lister states that 'This is a Japanese translation of the hard-backed edition of “The World of Origami”. It is a hard-backed volume of the same size as the English edition and with 264 pages. Most of the contents are the same, but there are minor changes and rearrangements.' (DL2) ********** 1970 `Publication of his book 'Origami Nippon' in Japanese. The majority of the designs in the book are drawn from Honda's standard repertoire but the work also includes diagrams for two simple variants of the Flapping Bird (the second credited to Toshio Chino), a box by Kunihiko Kasahara and Mitsunobu Sonobe's famous module and cube. Inter alia the Introduction says: 'I wanted to make origami more accessible to the masses ... and this book is my reflection on this, following traditional techniques while illustrating them in a way that is easy to understand and has a modern flair. By 'traditional techniques' Honda presumably means using straight line folds and cuts (where necessary to maintain simplicity) (possibly in contrast to Yoshizawa's softly creased, curved and crumpled approach). ********** Secondary Sources Isao Honda - Obituary written by David Lister, dated February 1976 (DL1) Isao Honda - An annotated list of his books written by David Lister, dated October 2005 (DL2), which gives information about many of Honda's books. Isao Honda's "How to Make Origami" written by David Lister, undated (DL3). Originally published to the Origami Mailing List, date not known. Isao Honda's "All About Origami" written by David Lister, undated (DL4). Originally published to the Origami Mailing List, date not known. Isao Honda's "World Of Origami" written by David Lister, undated (DL5). This is an amended and incomplerte version of a post with the same title made to the Origami Mailing List on 13th March 2002 (DL6). Article in the Origamian of Winter 1967 by Toshie Takahama titled 'Origami in Japan Today.' Noted here for completeness but does not add any information to that given in David Lister's writings. ********** |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||