| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 5/2/2025 x |

|||||||

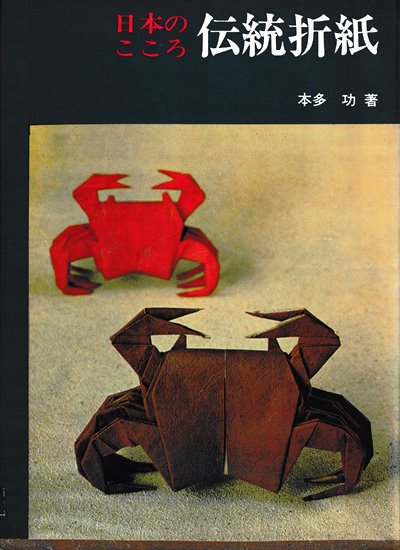

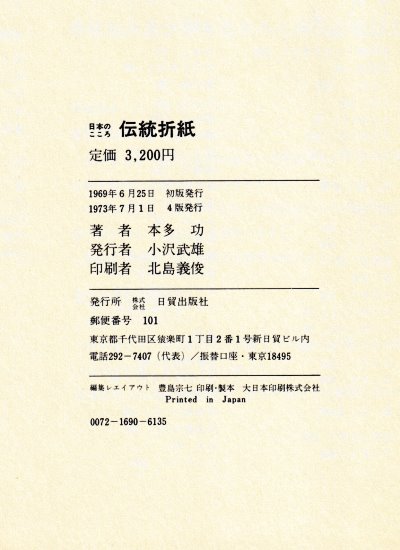

| Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami by Isao Honda, 1969 | |||||||

'Nihon no Kokoro Dento Origami' (Heart of Japan, Traditional Origami) by Isao Honda was published by Japan Publications in Tokyo in 1969. It is a Japanese language version of the hard-backed edition of the author's 'The World of Origami' (which was published in English in 1965). The information on this page is taken from the 4th edition of the work published in 1973, but I believe the content is identical to the original edition. This page only records those instances where this Japanese language version differs from the original work. The main differences between the works are found in the passages giving introductory, historical and technical informatiion. 'The World of Origami' was written for a Western audience who the author assumed, no doubt correctly, would not easily understand detailed references to Japanese history and culture. In this present work these passages have been rewritten for a Japanese audience. Full details are given below. The vast majority of the designs are the same as in the previous work, but, where there are significant differences, these are also detailed below. Other changes, such as the use of different photographs of the finished design or minor changes to the layout have not been recorded here. This work does not contain the Bibliographical Note which appears in 'The World of Origami'. Designs no 7: Hat, 11: Rabbit Hat and 12: Badger Hat which appeared in 'The World of Origami' were omitted from the Japanese version. NB: Designs which appear in both versions have only been listed under the earlier date in the relevant Index, Topic or Individual Design pages of this site. **********

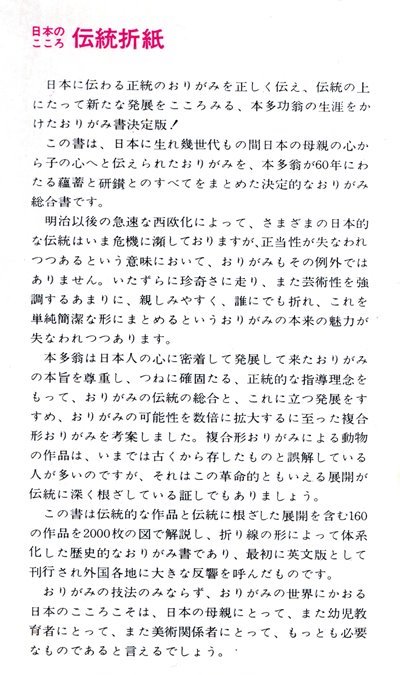

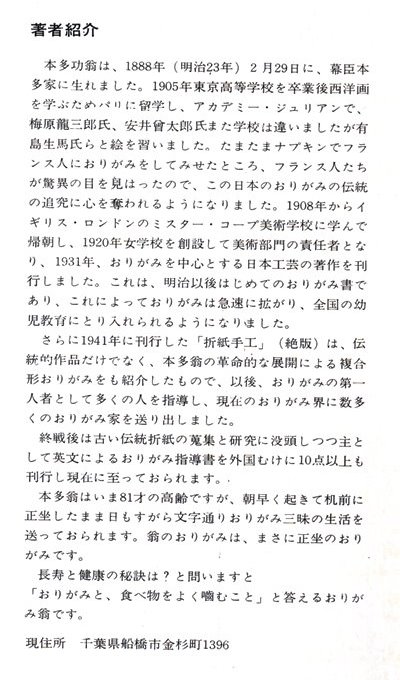

********** Information from the Dust Jacket Although this information on a dust jacket is written by the publisher rather than the author it does seem to me as though in this case the words have captured the essence of Isao Honda's beliefs about origami. Inter alia, and roughly translated: 'Due to the rapid Westernisation that began in the Meiji period, many Japanese traditions are now in danger, and origami is no exception, in the sense that its legitimacy is being lost. In an effort to be unnecessarily unusual and with too much emphasis on artistic value, origami's original appeal as something familiar, easy for anyone to fold, and easy to put together into simple concise shapes, is being lost. Honda respected the true essence of origami, which has developed in close contact with the hearts of Japanese people and always maintained a close and orthodox teaching philosophy. He promoted the synthesis of origami traditions and their development, and came up with compound origami, which expanded the possibilities of origami several fold. Many people mistakenly believe that animal creations made with compound origami have existed for a long time, but this is also proof that this revolutionary development is rooted in tradition.' The right hand page gives information about the author, including, inter alia and roughly translated:: 'Isao Honda was born on February 29th 1888 into the Honda family, a vassal of the Togukawa shoganate. After graduating from Tokyo High School in 1905 he went abroad to study Western painting. and studied under Umehara Ryuzaburo, Yasui Taro and Arishima Ikuma at the Academie Julian. By chance he demonstrated origami to some French people, using a napkin, who were amazed, and he became fascinated with the pursuit of this Japanese tradition. He also studied at Mr Cope's School of Art in London from 1908, then returned to Japan. In 1920 he founded a girl's school and became head of the art department. In 1931 he published a book on Japanese crafts, focussing on origami. This was the first book to be published since the Meiji era, and it led to the rapid spread of origami, with origami being incorporated into early childhood education throughout the country.'

********** The Author's Introduction Inter alia this introduction sets out some of the author's core beliefs about the origami tradition in Japan. Roughly translated: 'Origami ... this "paper craft game" has been passed down in a relay-like manner from mothers to children throughout the centuries of Japan's past, with new works reflecting each era being added along the way, and it can be said to be one of the cultural heritages unparalleled in the world. Rather than leaving this precious tradition as a classical relic, passing it on, while also developing it in new ways, can be said to be one of the duties that our ancestors have imposed on us.'

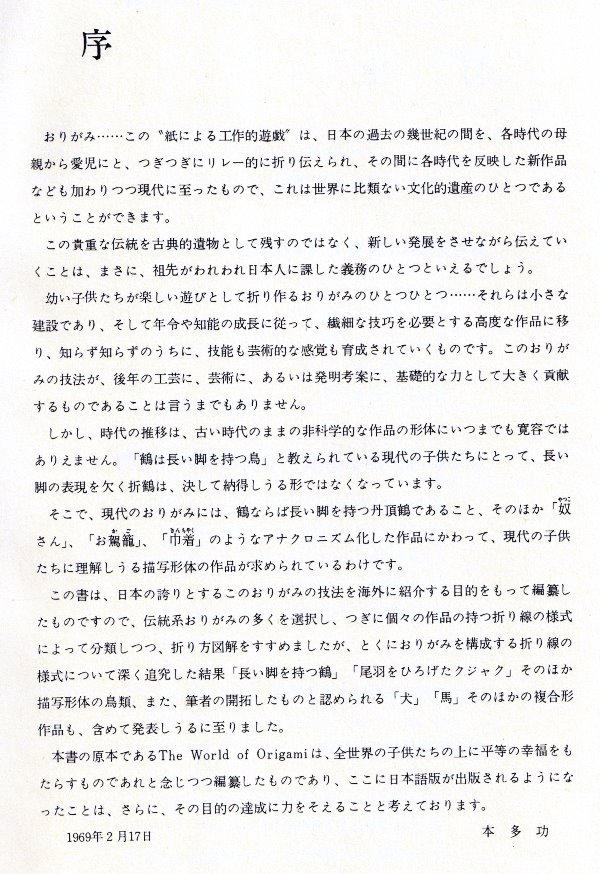

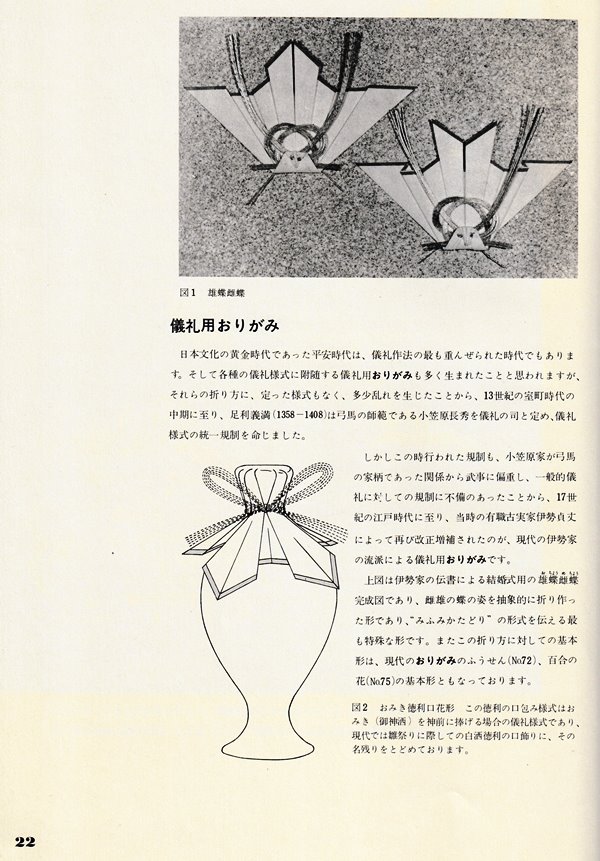

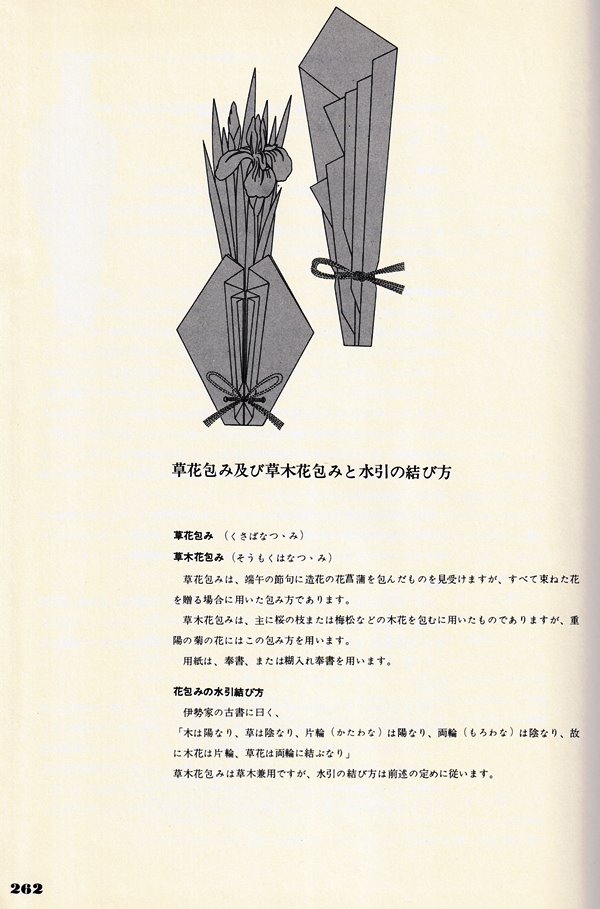

********** Selected Pages ********** The origin of Etiquettical Folding Roughly translated this section reads: 'The Heian Period, the golden age of Japanese culture, was also the time when ceremonial etiquette was most highly valued. It is believed that many ceremonial paperfolds were created to accompany various ceremonies. However, there was no set style for folding and some inconsistency arose. In the middle of the Muromachi period, in the 13th Century, Ashikaga Shikucho (1358 - 1408) appointed Ogasawara Nagahide, a mastery of archery and horse riding, as the head of ceremonies and ordered the unification of ceremonial styles. However, the regulations enacted at this time were biased towards the martial arts ... and the regulations for general ceremonies were inadequate. As a result, in the 17th Century Edo Period, the regulations were revised and and expanded by the court noble Ise Shinjo, and what we know today is the Ise school of ceremonial origami.' Sake bottle covers and decorations Roughly translated this section reads: 'This style of tokkuri (sake bottle) rim wrapping is a ceremonial style used when offering omiki (sacred sake) to the altar, and remnants of this style can still be seen in the rim decorations on sake tokkuri used during the Hinamatsuri festival.'

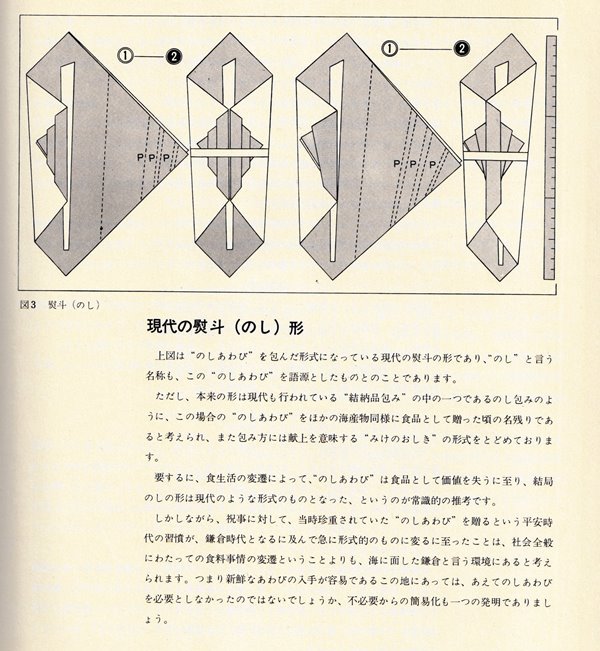

********** Noshi

********** The Kan No Mado Inter alia this section says, roughly translated: 'Origami is becoming increasingly popular in the world, and there is so much enthusiasm that there is even a research group in New York called the Origami Society, whose members include Mrs Oppenheimer. Recently, however, a type of origami called Kan no mado, which has been discovered in old Japanese manuscripts, has become a major issue among members of this group. It is a technique that apparently first involves cutting the paper into an irregular hexagon with deep slits, then folding it, and the diagrams illustrating over a dozen folding methods, including the 'tomba' type, are drawn in calligraphy and are extremely incomprehensible. Not only that, the explanations of the diagrams are written in old-fashioned Japanese, and even Japanese people living in Japan are unable to decipher them ...' 'During the Taisho era the 'Seshafuda Dance' became popular, and among these people was an elderly American gentleman, dressed in traditional Japanese clothing, who would travel around the country pasting pilgrimage tags ... at shrines and temples. This man was Dr Frederick Starr, a Japanophile known as the 'Banknote Doctor'. He passed away in 1933, but the various Japanese documents he collected during his time in Japan are preserved in the United States ... and the 'Kan no mado' was discovered within this collection.' The final paragraph of this section talks about Yoshimichi Rokoan and his two books Senbazuru Orikata and Orikata Tehon Chushingura, both published in 1797. Honda mentions a third book by the same author, called 'Shinsen Origata Zue' and adds, roughly translated: 'In one corner of the illustrated Chushingura book there is a notice about the publication of this book but it has remained undiscovered to this day.'

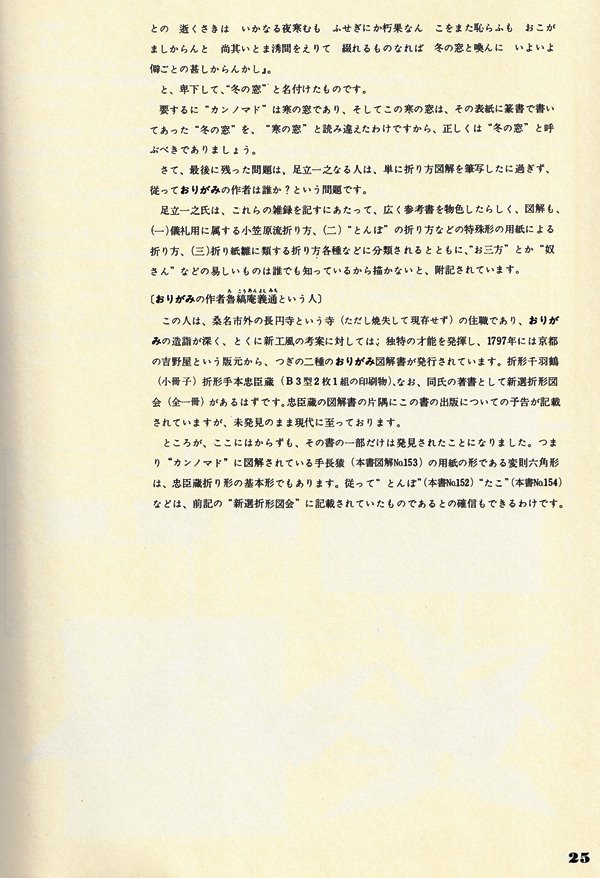

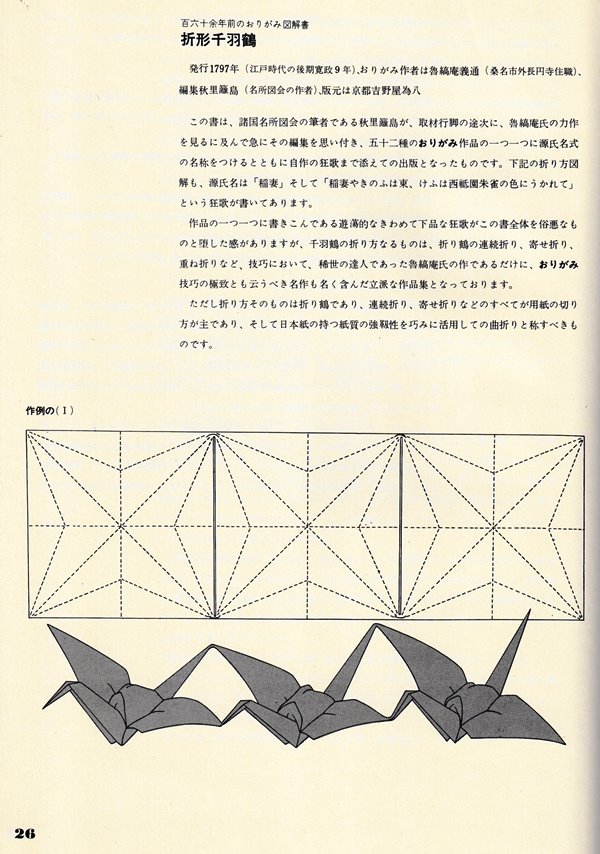

********** The Senbazuru Orikata Honda says, roughly translated: 'This book was published by Akisato Rito, author of 'Shokuko Meishi Zue' (Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Various Provinces) who came up with the idea of compiling it after seeing the plan of each masterpiece during a pilgrimage. He gave each of the 52 origami works a name based on their geisha name and even included his own kyoka (comic poems). The geisha name for the folding diagram below is 'Lightning' and the kyoka is 'Lightning, yesterday was the East, today in the West garden I am enchanted by the colour of the Vermillion Bird'. The extremely vulgar, leisurely kyoka poems that accompany each and every design give the book as a whole an air of vulgarity ...'

********** In the folding instructions for this design, titled 'Horai', Honda recommends to 'reinforce the connecting points with cellophane tape'

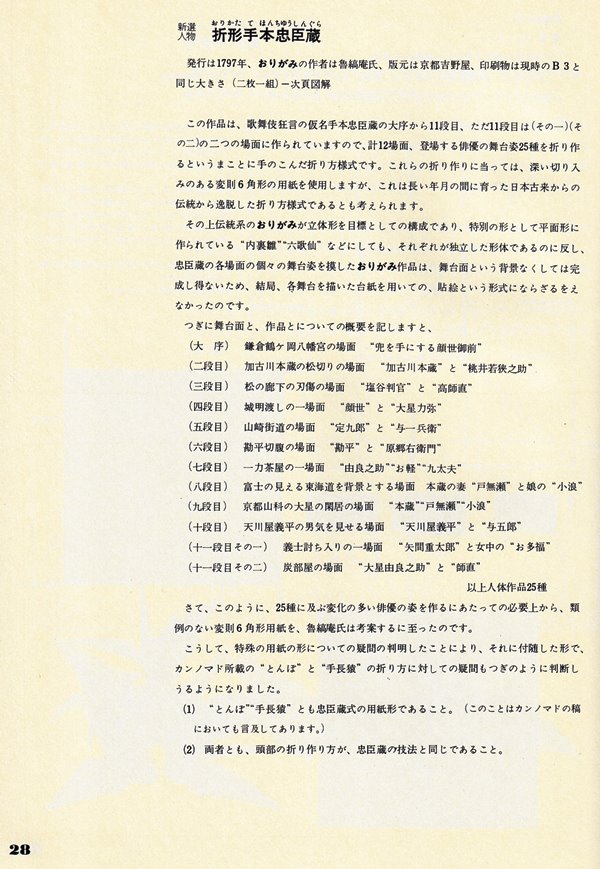

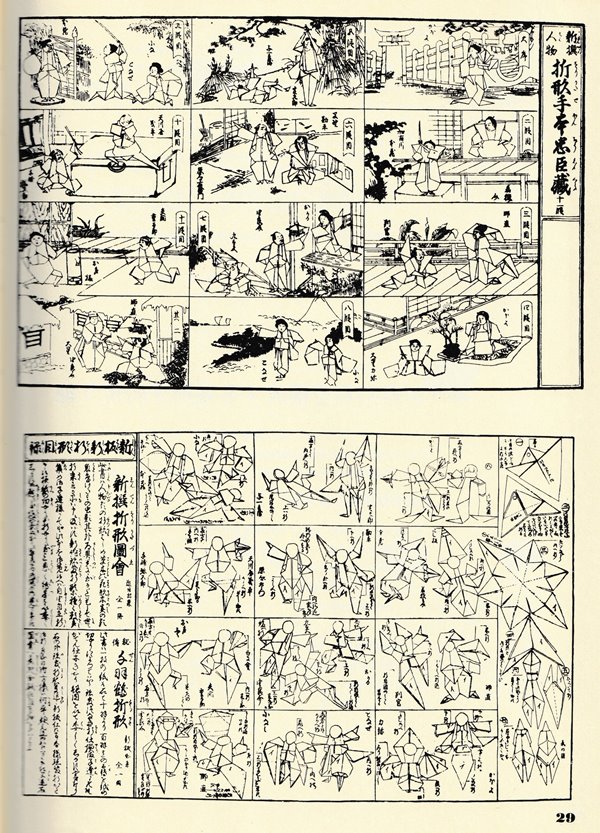

********** The Orikata Tehon Chushingura Honda says, roughly translated '... this folding style can be considered to be a deviation from the ancient Japanese tradition that has been developed over many years. Furthermore, traditional origami is composed with thge goal of creating three-dimensional shapes, and even special pieces, such as 'The Six Poets of the Imperial Court', which are made into flat shapes, are independent of each other. However, the origami works that imitate the individual stages of each scene from Chushingura cannot be completed without the background, so in the end they had to be in the form of collages, using mounts ...' 'Now the need to create 25 differentposes for the actors led (the author) to come up with the unique hexagonal paper ...' and 'It seems likely that the Orikata Tehon Chushingura that was sold was merely an illustrated book that no one could fold.'

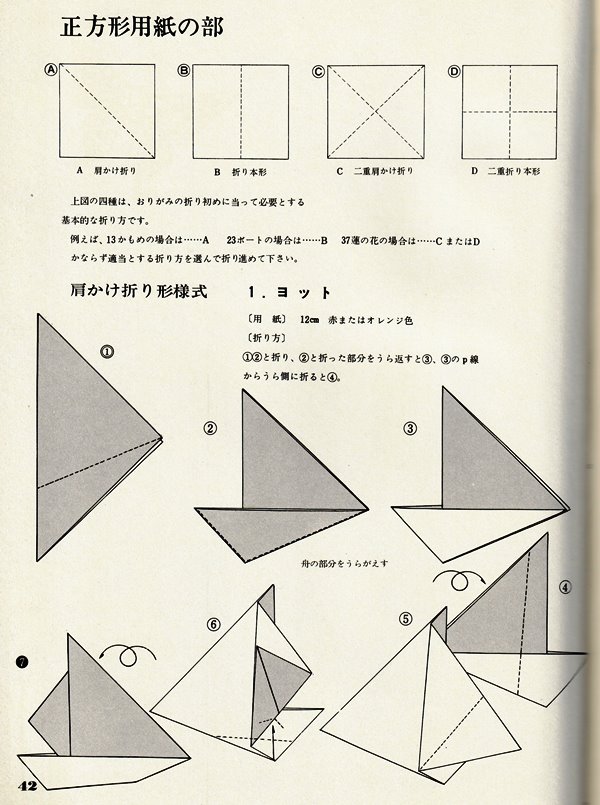

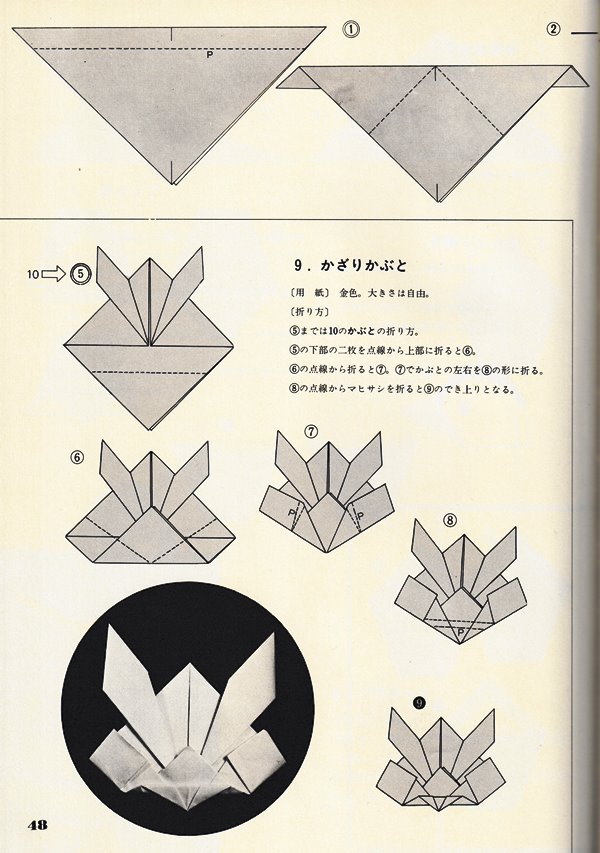

********** 1, A more complex form of The Yacht

********** 2. A more complex form of The Long-Horned Kabuto

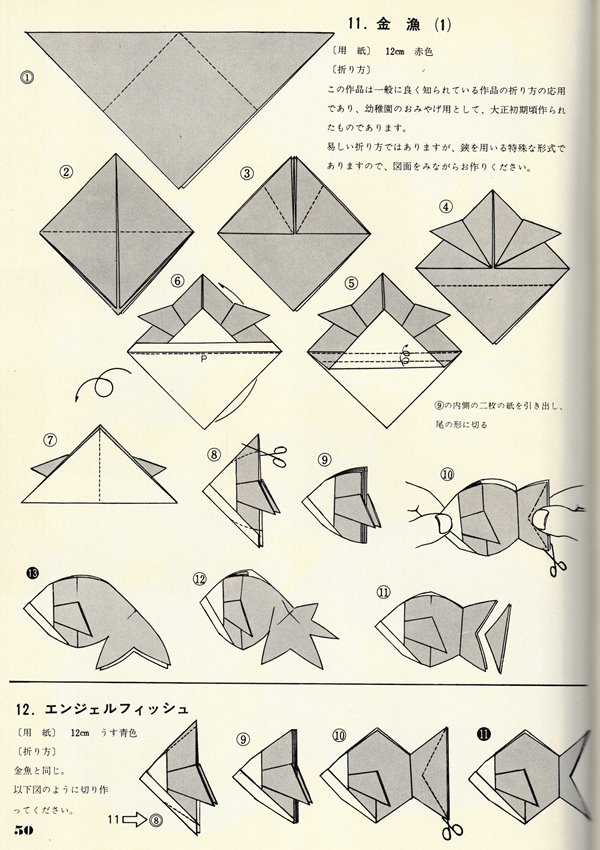

********** 11. Two variations of The Cut Goldfish The wording says, roughly translated: 'This design is an application of a commonly known folding technique and was made in the early Taisho period (1912 to 1926) as a kindergarten souvenir'.

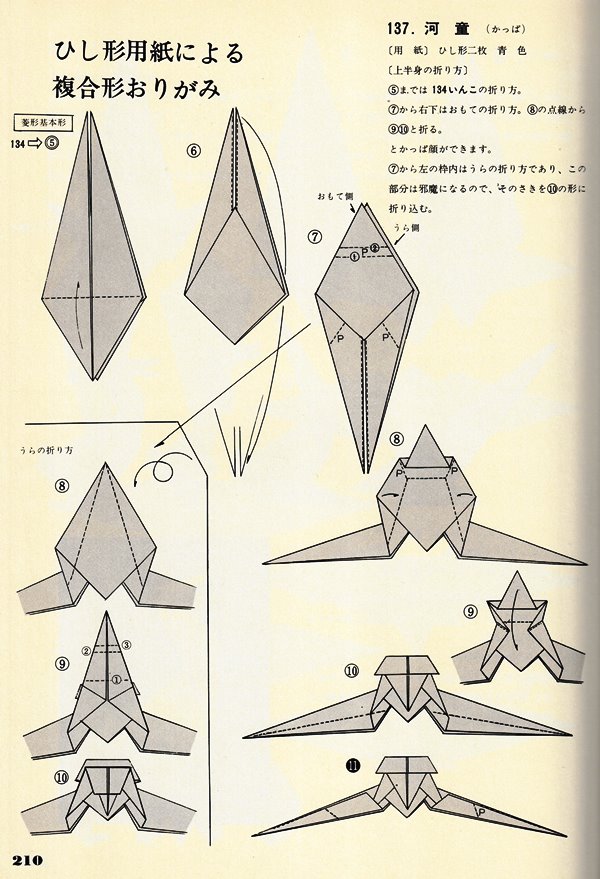

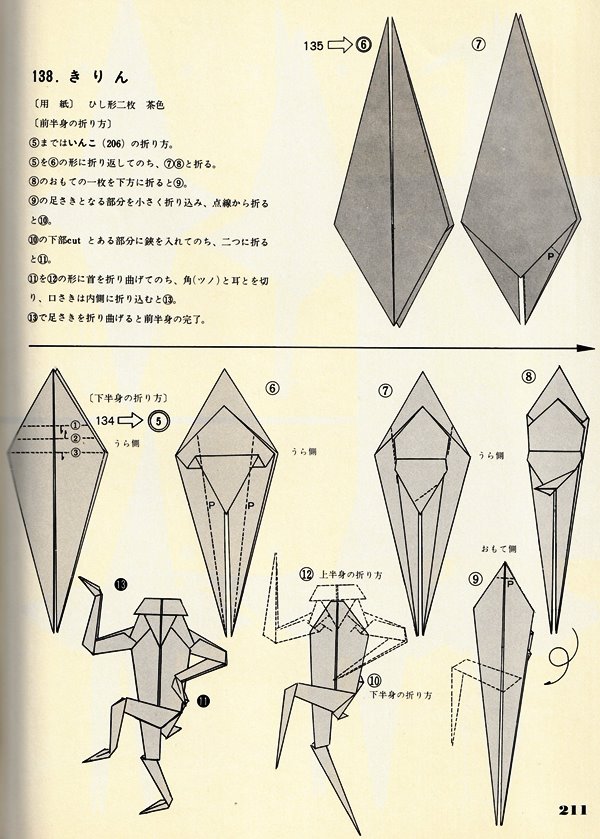

********** 137. Kappa from two rhombuses. A 'kappa' is a mischievous water spirit.

**********

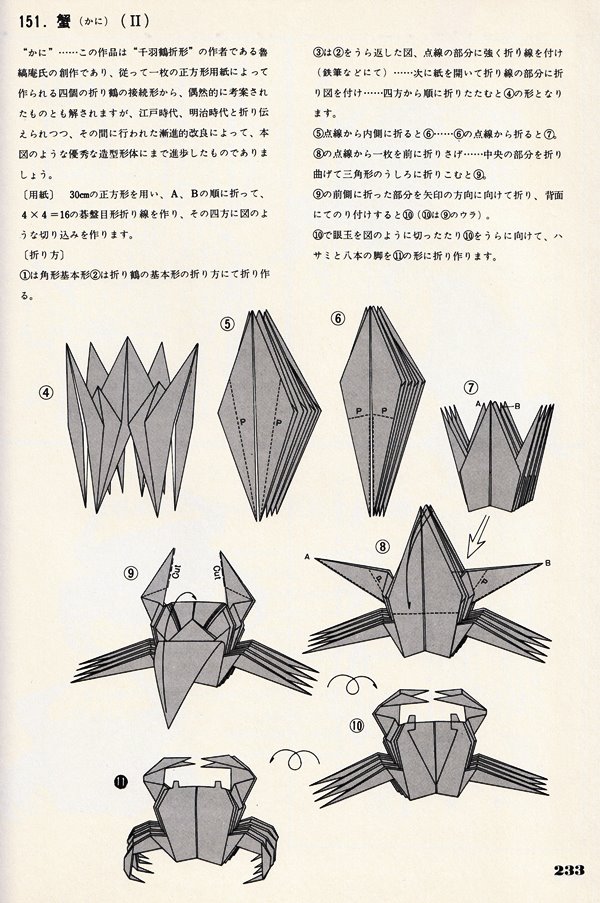

********** 151. Crab (Cut) - The Kan No Mado Crab Of this design Honda says, roughly translated: 'This piece was created by the author of the 'Senbazuru Orikata' and therefore it can be interpreted as having been devised by chance from the connected shape of four folded cranes made from a single square piece of paper. However, as it was passed down through the Edo and Meiji periods, gradual improvements were made during that time and it likely evolved into the excellent form seen here'. The author does not give any evidence for his belief that it was created by the author of the 'Senbazuru Orikata'.

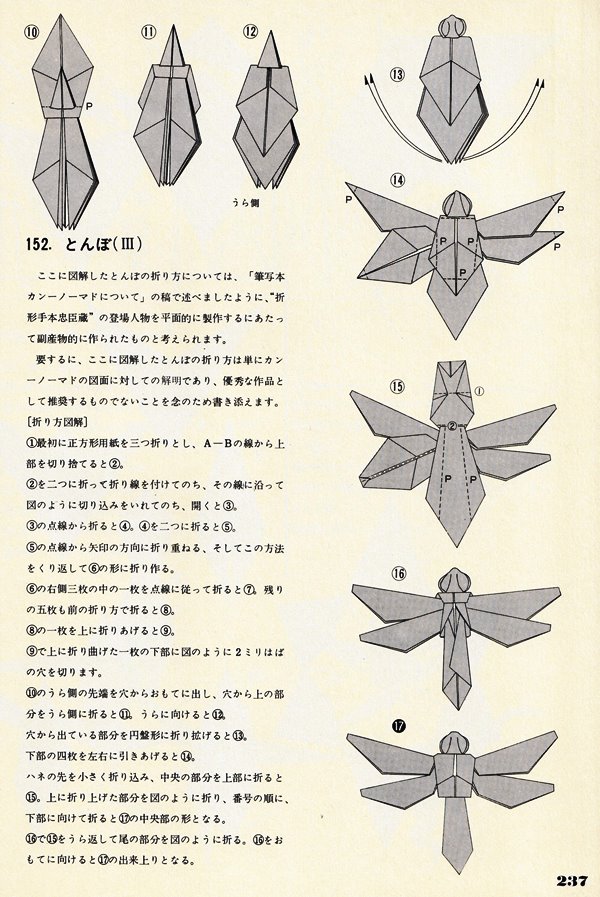

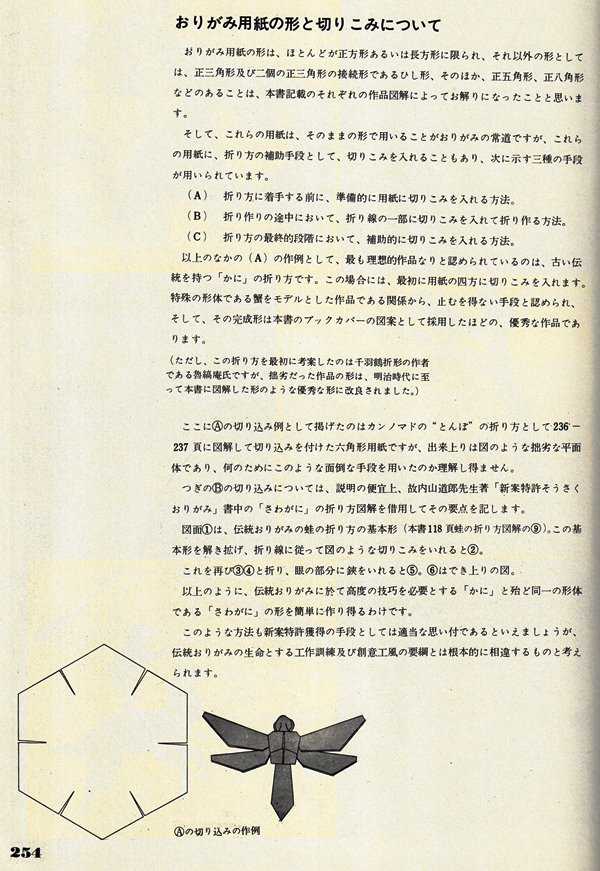

********** Reconstruction of the Kan No Mado Dragonfly About this figure the author says, roughly translated: 'As mentioned in the article 'About the Kan No Mado Manuscript' the tonba folding method illustrated here is thought to have been created as a by-product of creating two-dimensional figures of the characters in 'Orikata Tehon Chushingura. I would like to make it clear that the tonba folding method illustrated here is merely an explanation of the Kan No Mado's drawings and is not something I would recommend as an excellent work of art.'

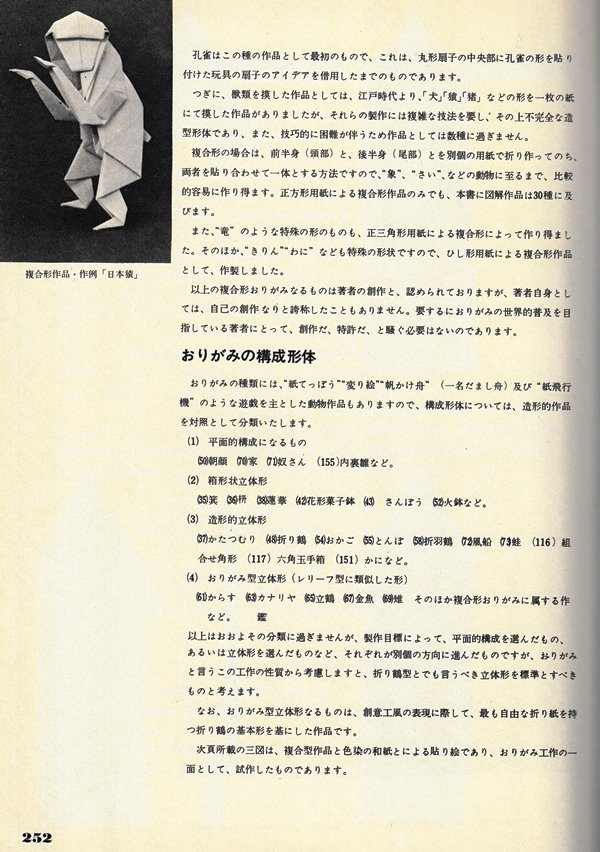

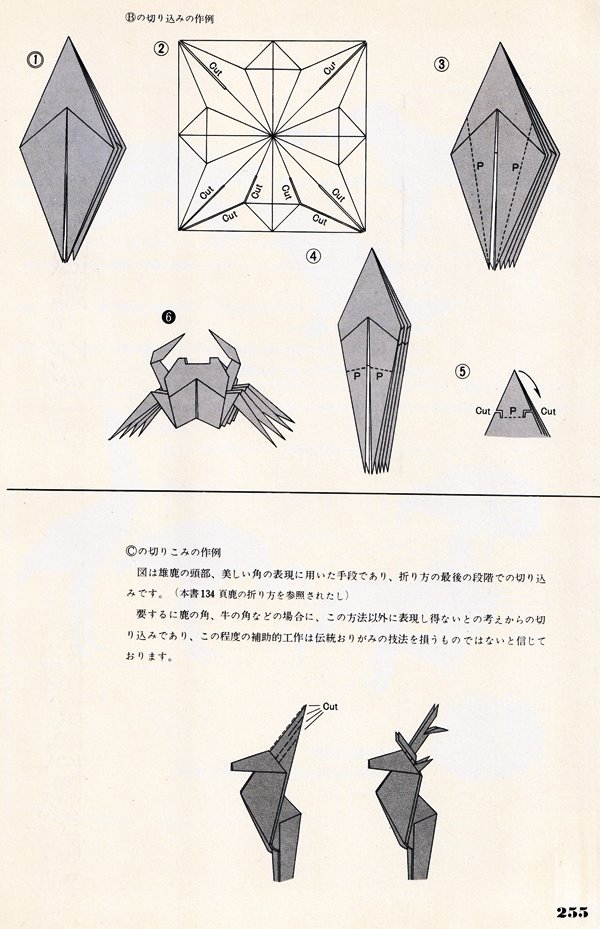

********** A vision for modern origami Much of this section is difficult to understand and I have just selected a few interesting statements to highlight here. The opening paragraphs read, roughly translated: 'When we look at traditional origami, especially origami from the end of the Edo period through to the Meiji period, we can see that consideration was given to relatively easy folding methods for young children. For example 'Yakkosan' and 'Fukusuke' are thought to have been names given to shapes created by folding dolls in a very formal way, but the reason why such childish shapes became popular nationwide is probably because theyt served as supplementaryeducational materials to the art of folding dolls, which was one of the important educational programmes imposed upon girls at the time.' Honda's ideas for modernising origami, which he felt had become outdated, seems to have been first to change the names of some traditional designs to new ones that children could relate to more easily, thus, for instance, 'yakkosan' became 'scarecrow' and then to simplify the folding / cutting methodologies, particularly by the introduction of his compound technique, but much of what he says about this I cannot understand.. Inter alia Honda also says, roughly translated: 'I would like to state that the first works based on this concept (ie making a compound design from two folded sheets) were the 'Peacock' and 'Horse' published in the 1941 issue of 'Origami Handicraft' (published by Kogyo Co Ltd, the predecessor of the current Sangyo Co Ltd).' He also states: 'The above composite works are recognised as new works by the author, but the author himself has never called them his own creations. In short, for the author who aims to popularise origami worldwide, there is no need to make a fuss about creation or patent.' The crab at the foot of this section is a design by Michio Uchiyama.

**********

**********

**********

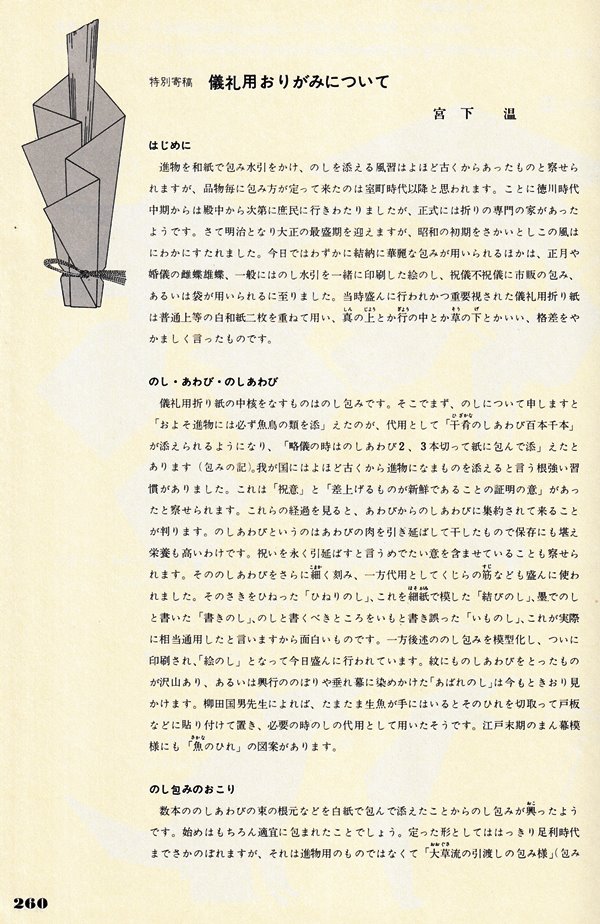

********** An article 'About Special Ceremonial Origami' written by Atsushi Miyashita. The first paragraph says, roughly translated: 'The custom of wrapping gifts in washi paper, tying it with mizuhiki and attaching a noshi ... seems to have existed for a very long time, but it seems that it was only after the Muromachi period that the way of wrapping each item was established, in particular from the mids-Tokugawa period, it gradually spread freom the Imperial court to thecommon people, but officially there seems to have been a specialised folding school. It reacxhed its peak dsuring the Meiji and Taisho periods, but suddenly went out of fashion around the beginning of the Showa period. Today, apart from the occasional use of ornate wrapping for betrothal gifts, the female and male butterfly wrapping for New Year's and weddings ... and commerecially available wrapping or bags for congratulatory or non-condolence gifts ...'

**********

**********

********** The Origins and Traditions of Origami The second paragraph reads, roughly translated, 'In 1936 I was asked by a Canadian publisher to write a book titled 'How to make Origami'. The Preface to the book was written by Mrs Oppenheimer, a well-known American researcher in origami. I was taken aback by a passage in the Preface that categorically stated 'The technology of origami was brought to Japan from China along with the method of making paper, at the beginning of the 6th Century' However, later, through documents from her, it became clear that the theory that origami was introduced from China was actually due to an article in a Japanese encyclopaedia. The method of cutting Katashiro, which was introduced along with Buddhism, was reported as if it was the first origami, and this eventually led to the theory that origami was introduced from China'. Katashiro are paper dolls said to be inhabited by Kami (spirits). He also says: 'I believe the word 'art' in the description 'the art of japanese paper folding' should not be rendered as 'art' but as 'technology'.

********** |

|||||||