| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 18/3/2024 x |

|||||||

| A Brief History of Educational, Decorative and Recreational Paperfolding In Europe and the Americas to the Death of Froebel in 1852 | |||||||

By educational paperfolding I mean paperfolding intended to act as a means of education. By decorative paperfolding I mean paperfolding used to create items intended to be used as ornaments or decorations for the home or elsewhere. By recreational paperfolding I mean the activity of folding paper to amuse or entertain oneself or others, or to create toys or puzzles or to facilitate the playing of games. ********** A: The Catherine of Cleves Box The magnificent Flemish illustrated manuscript known as The Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves, which dates to c1440, contains several illustrations of a sophisticated cut-and-fold box at the bottom of a page devoted to St Agatha. The pictures clearly show how the box is constructed but there is no textual evidence of the material used. This box should clearly be classed as a practical paperfold but I have included it here because it became popular as a recreational paperfold in the 19th century.

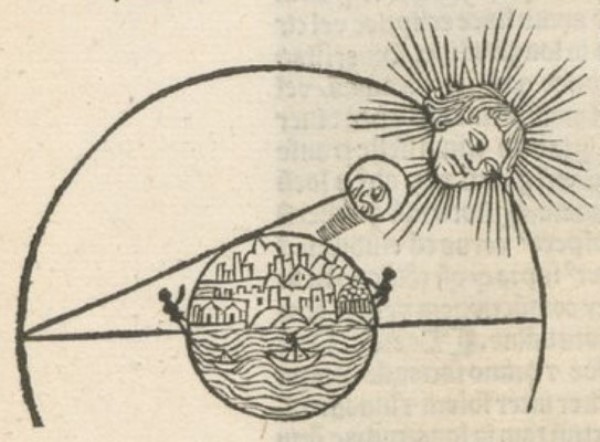

Page devoted to St Agatha in 'The Hours of Catherine of Cleves' ********** A picture illustrating a solar eclipse which seems to show two Paper Boats floating in a stylised sea, appears in 'Uberrimum sphere mundi commentum intersertis etiam questionibus domini Petri de Aliaco', which was published in Paris in 1498 by Guy Marchant for himself and Jean Petit. This book is a version of the much earlier book 'Tractatus de Sphaera Mundi' by Johannes de Sacrobosco (a name used by John Holywood, an English mathematician and astronomer). It is difficult to imagine what else could be being represented here, but, for lack of any confirmatory text, we cannot be completely certain that this is what the illustrator was intending to depict.

If it is the Paper Boat that is depicted here, it is somewhat surprising that the next indisputable reference to the design does not appear until 1840, well over 200 years later, when diagrams were published in the 'The School Boy's Holiday Companion' by Thomas Kentish. There are a few references to paper boats in Western European literature which predate this. For instance: There is reference to a paper boat being used to help demonstrate that a magnetised needle will default to point north / south in 'The Navigator's Assistant' by William Nicholson, which was published in London in 1784. In 1808, Jane Austen wrote a letter to her sister Cassandra which included two references to paper ships, of some undefined kind. Also, according to his friend and biographer Thomas Jefferson Hogg, the romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 - 1822) had a passion for folding and sailing paper boats, which he made from any paper which was at hand, including letters and the flyleaves of books. However, in all these cases, because of lack of good descriptions or illustrations, it is not possible to confirm which design of paper boat is being referred to. ********** 'De Viribus Quantitatis' by Luca Pacioli was written c1496 to1508. It is fundamentally a book of mathematical puzzles but includes a section describing several paperfolding designs. Some of these are purely practical designs, but there are others which we might consider recreational. This is the first appearance of this classic puzzle, which is both set and solved by folding the paper. It appears frequently thereafter in many other books.

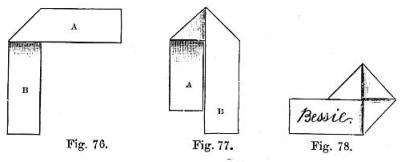

Illustration from 'Jeux et Jouet du Jeune Age' by Gaston Tissandier, published in 1884, ********** The book gives several ways to seal a letter without using wax, one of which is to fold the letter into a long, thin strip and then weave the strip into a square. If the ends were not tucked in to create the square this design would be the same as the Love Knot Letterfold.

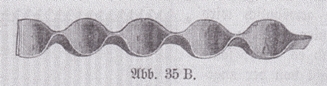

An illustration of the design, without the ends tucked in, from 'Pleasant Work for Busy Fingers' by Maggie Browne,which was published in 1891. ********** iii. The Chickenwire Letterfold The book also describes another way of sealing a letter without wax which seems to me to be a good description of how to create the Chickenwire Letterfold.

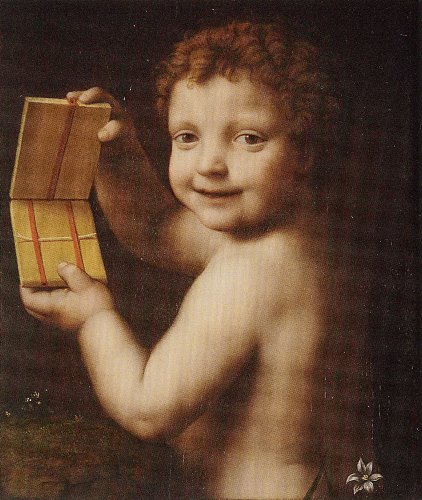

Illustration from 'Des Kindes Erste Beschaftigungsbuch' by E Barth and W Niederley, which was published in 1876. ********** This book also contains the earliest known description of the Chinese Wallet toy (which is not in any way Chinese). While not itself made of folded paper this device is a forerunner of what we now know as tetraflexagons. The Chinese Wallet is also shown in this painting by the Italian painter Bernadino Luini (1470 - 1533) which can be dated to around 1515.

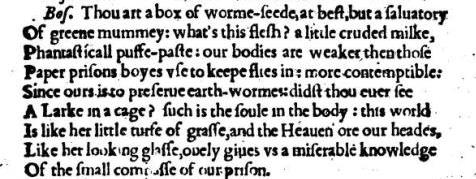

********** D: Stunts, tricks and entertainments in books of 'natural magic' Much of the early evidence (though not all) for a European tradition of recreational paperfolding comes from early books about 'natural magic' (ie science, particularly chemistry), although they also include some puzzles, mathematical items, and practical stunts and novelties of all kinds. In effect they are compendiums or miscellenea of anything the authors thought might be of interest to their readers. In chronological order from 1584 to 1852 these books about 'natural magic' are: Magiae Naturalis by Giambattista della Porta, 1584 Deliciae physico mathematicae by Daniel Schwenter, 1636 Deliciae physico mathematicae Volume 2 by Georg Phillip Harsdorffer, 1651 Deliciae physico mathematicae Volume 3 by Georg Phillip Harsdorffer, 1653 Natural Magick by John Baptista Porta, 1658 Joco-seriorum naturae et artis by Gaspar Schott, 1666 Het natuurlyk tover-boek by Simon Witgeest, 1684 and 1686 Neueröffnete Raritäten und Kunst-Kammer by Simon Witgeest, 1702 Natürliches Zauber-Buch oder neuer Spiel-Platz der Kunste by Simon Witgeest, 1707 Récréations mathématiques et physiques by Jacques Ozanam, 1723 Enganos a Ojos Vistas, Y Diversion de Trabajos by Pablo Minguet E Irol, 1733 I Giochi Numerici Fatti Arcani by Giuseppe Antonio Alberti, 1747 Tresor des Jeux by Carlo Antonio, 1759 Die Zehenmal Hundert und Eine Kunst by Albrecht Ernst Friedrich von Crailsheim, 1762 Künste und Geheimnisse von Philadelphia zur Belastigung Jedermanns, 1785 Der magische Jugendfreund by Johann Heinrich Moritz von Poppe, 1817 Neuer Wunder-Schauplatz der Kunste by Johann Heinrich Moritz von Poppe, 1839 El Brujo en Sociedad by D J Mieg, 1839 Das Buch der Zauberei by Johann August Donndorff, 1839 These books all draw from the same set of effects, though not all the effects are present in every book. The main items of relevance to paperfolding history are explained below. It is interesting to note that almost all of these early designs are folded from oblongs rather than squares, the exception being the Buddha Papers (which can also be folded from oblongs). ********** This magic effect is first mentioned in Book 20 of 'Magiae Naturalis' by Giambattista della Porta (1535-1615) which was published in 1584. The three scrolls are placed together and rolled up. When unrolled they are found to have changed places relative to each other. ********** 1584 saw the publication of the book 'The Discoverie of Witchcraft' by Reginald Scott which included an explanation of two simple magical effects using folded paper, the Fold and Switch Effect and the Buddha Papers, variations of both of which are still in use by conjurors today. The Buddha Papers effect is particularly interesting. It uses two squares folded into thirds in both directions, then into packages, which are glued back to back. Some small object placed in one package can be shown to have vanished by opening the other, the audience, of course, being unaware that more than one package exists. ********** iii. Paper Prisons for Flies There is a line in John Webster's play ‘The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy', which was first published in London in 1623. It contains a speech referring to 'those Paper prisons boys use to keepe flies in'.

We do not know what kind of paper prison John Webster had in mind when he wrote those words. It has sometimes been taken as a reference to the Waterbomb design, which has certainly been used to imprison flies in more recent times, but, for lack of either a description or an an illustration it is impossible to say whether this is the case or not. Any kind of closed paper container, such as, for instance, a paper cone twisted shut at its open end could act as a paper prison for flies, or other insects, in a similar way. Indeed, there is no need for such a paper prison to be closed. 'The Boy's Own Book' by William Clarke, which was was published in London in 1828, contains details of a stunt in which a sheet of paper that had been rolled into a cone could be placed over an insect on a table to entrap it. Presumably any open-topped box, if turned upside down, could also act as a paper prison in this way.

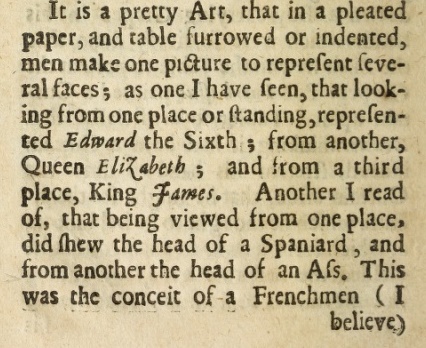

The first definitive evidence for the existence of the Waterbomb design does not appear until 1863, when diagrams were published in Amsterdam in 'De Kleine Papierwerkers 1: Wat men van een stukje papier al maken kan: Het vouwen' (The Small Paperwork 1: What one can make from a piece of paper: Folding) by Elise Van Calcar. ********** iv. Multiple-Image Pleated Paper Pictures / Falzbilder / Tabulae Striatae 'Deliciae physico mathematicae oder mathematische und philosophische Erquickstunden' by Daniel Schwenter, which was published in 1636 contained a section on tabulae striatae made from wooden slats.The earliest reference to the pleated paper version that I know of is found in 'Humane Industry' by Thomas Powell which was published in London in 1661.

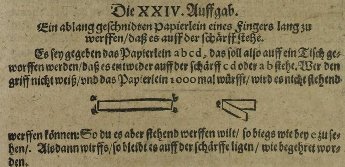

********** This design appears in the 1684 edition of 'Het natuurlyk tover-boek' by Simon Witgeest. This primitive banger is constructed and performed by folding a sheet of oblong paper in half and then in half again, grasping the middle two layers and making a sharp throwing motion with the hand. ********** vi. How to climb through a playing card The fold, slit and fold method, that we have already met in connection with practical paperfolding designs, was also used to create recreational designs such as the design commonly known today as the ‘How to Climb Through a Playing Card’ effect, and which first appeared in in 'The Merry Companion' by Richard Neve, which was published in London in 1716. ********** vii. How to Drop a Strip of Paper to Land on One Edge This very simple challenge, which is solved by folding a strip of paper in half widthways, first appears in 'Deliciae physico-mathematicae, oder mathematische und philosophische Erquickstunden' by Daniel Schwenter, which was first published in 1636.

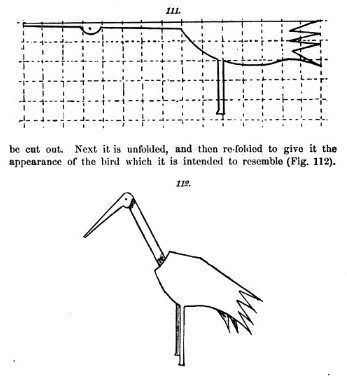

********** viii. Symmetrical Fold, Cut and Fold Animals The earliest reference to this kind of paperfolding appears in Part 4 of 'Die Zehenmal Hundert und Eine Kunst' by Albrecht Ernst Friedrich von Crailsheim, which was published in 1762. The relevant text says, roughly, 'Fold a piece of paper in two, then cut out a bird, a turtle, or whatever you like and glue a fly in the middle of it with wax ...', the idea being that the the bird or turtle etc then appears to walk around the top of a table under fly power. Several examples of this type of design appear in 'The Kindergarten Guide' by Maria Kraus Boelte and John Kraus, which was first published in New York in 1882. By this time the designs had become more sophisticated and they were often folded again after they had been cut out to make them look much more realistic

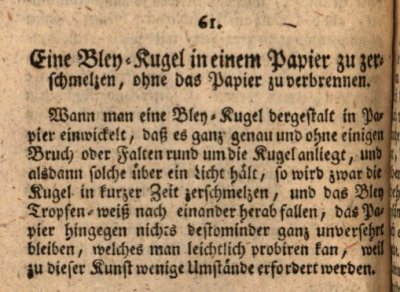

********** This is a magic stunt (or if you prefer, a scientific experiment) in which a lead ball is wrapped in paper and held over a flame, the lead melting a runningout of the paper before the paper catches fire. As far as I know a description of this effect first appears in part two of 'Die Zehenmal Hundert und Eine Kunst' by Albrecht Ernst Friedrich von Crailsheim, which was published in 1762.

********** The earliest reference to Paper Filigree / Quilling that I know of is a section titled (in translation) 'How to Make Baskets out of Rolled Paper' in Part Five of 'Die Zehenmal Hundert und Eine Kunst' by Albrecht Ernst Friedrich von Crailsheim, which was published in 1762. The making of a paper filigree basket also features in Jane Austen's novel 'Sense and Sensibility', first published, anonymously, in 1811. ********** xi. A Purse in the Shape of a Rose with Twelve Leaves Part 6 of 'Die Zehenmal Hundert und Eine Kunst' by Albrecht Ernst Friedrich von Crailsheim, also published in 1762, contains instructions for making a complex collapsible purse in the shape of a rose with twelve leaves.

********** This design is first known from two letters folded into pentagonal knots, which have survived in an archive in France and can be dated to 1668. A description of how to fold a pentagonal knot appears in the 1682 second edition of 'Trattato Della Sfera' in a section called 'Prattische Astronomonische. Intorno all circoli della Sfera' which was an addition to the original work by Urban d'Aviso. ********** 'Les Jeux et Plaisirs de l'Enfance' which was published in 1657 contains 50 engravings of naked boys engaged in playing various, often very robust, games, one of which shows them playing darts. The flights look as though they could well be made of paper, possibly from a square folded into a waterbomb base, although there is no text to confirm this.

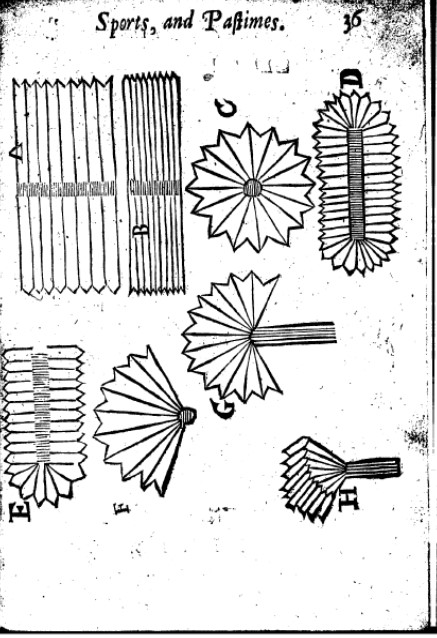

Very similar darts with flights made from waterbomb bases appear in the mid 19th century as part of the game known as Dart and Target. As far as I know this is the earliest example of a design that can only be folded from a square. ********** G. Troublewit Troublewit is a paperfolding based entertainment in which a large pleated sheet of paper is transformed into a variety of complicated three-dimensional forms. The earliest description of Troublewit appears in the book 'Sports and Pastimes: or, Sport for the City, and Pastime for the Country; With a touch of Hocus Pocus, or Leger-demain: Fitted for the delight and recreation of Youth' which was printed by H. B. for John Clark, at the Bible and Harp in West-Smithfield, London in 1676. The introductory sentence reads 'Trouble-wit has not its name for nought, and indeed is a very fine invention, by folding a sheet of Paper, as that by Art you may change it into twenty-six several forms or fashions'. Troublewit subsequently featured in many other books about conjuring, and in a number of the 'natural magic' books listed above.

A page from 'Sports and Pastimes' showing several Troublewit forms ********** H: Napkin and tablecloth folding In the 17th century a practice developed in Italy of folding tablecloths and napkins into fantastical forms to act as decorations for banqueting tables. This type of folding was, naturally, reserved for the houses, or palaces, of the very wealthy. Explanations for making these fantastical forms first appear in 'Trattato delle piegature', by Mattia Giegher, which was published in 1629. Some similar designs are featured in 'Aanhangzel volmaakte Hollandsche keuken-meid' (the perfect Dutch kitchen-maid) by Jan Willem Claus van Laar, which was published in Amsterdam in 1746, but thereafter it seems to appear in the culinary literature only as a memory of past glories.

A plate from 'Trattato delle piegature' by Matthia Giegher, published in 1629 However, a second type of napkin folding, first evidenced from 'Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch' by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer in 1652, in which small napkins, those intended to be used by the diners, were folded into holders for bread rolls, or place decorations, has survived much longer.

Plates from 'Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch' by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, published in 1652 This second type of napkin folding has clear similarities to paperfolding and some of its forms, such as the 'Croix de Sainct Esprit' (the Triple Blintz Basic Form) and the 'Croix de Lorraine' (the Cross), both first evidenced from 'Escole parfaite des officiers de bouche', which was published in 1662, appear to have crossed over into the recreational paperfolding repertoire at a later date. ********** I: Toys made from folded playing cards Simple recreational paperfolding designs folded from playing cards appear in the early 18th century. La Voiture de Cartes is evidenced from 1725, card castles built using folded cards from c1735, folded cards being used as skittles from around the same date, the Playing Card Cube from 1759 and the Playing Card Monk (or Capuchin de Carte) from 1760. This is still, of course, not quite recreational paperfolding as we know it today, since the main recreational aspect was the use of the cards as toys after they were folded, and not the paperfolding itself. However, it is interesting to see that folded paper (playing cards were made by laminating several layers of paper together) had become an acceptable form of plaything, at least among the wealthy upper classes. As far as I know this design first appears in this engraving by Francois Joullain after Charles Antoine Coypel, which shows a child building a Card Castle. The Voiture de Cartes design, not a boat but a cart without wheels, made from two folded playing cards, is in the foreground. A card at the lower left bears the words 'Car Coypel 1725', thus giving us the date of the original painting, which appears to have been lost. Several later painted versions and at least one other print are in existence.

********** ii. Card Castles We first hear of these in an entry for 6th October 1606 in the journal of Jean Heroard who was the personal doctor of the young Louis XIII. The relevant part of the entry reads 'il s'amuse a faire des chateaux de cartes', in English 'he amused himself making card castles'. Most card castles that we can see in paintings and engravings from the 18th Century were built, as they still are, using unfolded cards, but we know from an engraving by Jean Michel Liotard from 1744 that folded cards could also be used.

********** iii. Playing Card Skittles Folded cards were also sometimes used as skittles, in the way we use dominoes today, so that if one was pushed over all the others fell in turn. Lines of folded cards are shown in several paintings but the idea is particularly clear in this painting from 1871 by the German painter Johann Ernst Heinsius.

********** The most interesting of the designs made using folded playing cards that emerged during this period was, however, the Playing Card Cube, in which sets of six folded playing cards go together to form cubes, which can then be joined together into larger structures by interlocking their external tabs. These cubes appear in several paintings and prints made during the 18th Century, the clearest, though not the earliest, of which is shown below. The painter is unknown but possibly Louis Joseph Watteau (1731 - 1798).

********** v. Playing Card Monks / Capucins de Cartes By folding a card in half, cutting a slit in the folded edge, and folding the top half upwards, it was possible to create a hooded figure that looked like a capuchin monk. These Playing Card Monks or Capuchins de Cartes also appear in several paintings from the 18th Century, the earliest of which is a watercolour entitled 'Le Petit de Chevilly et Sa Soeur' by Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle which can be dated to somewhere between 1740 and 1760. Playing Card Monks were also used as skittles and the phrase 'tombent comme des capucins de cartes' became something of a cliche in France.

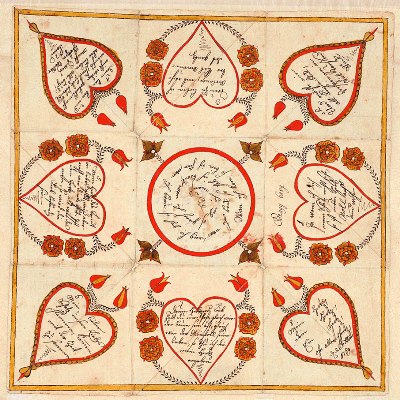

Detail from 'Le Petit de Chevilly et sa Soeur' ********** The earliest evidence for this design that I can find outside Japan (where it is known as the Thread Container - see above) is a liebesbrief (love letter) in the collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia dated to 26th December 1769. (The date is in the bottom right corner of the illustration below.) The crease lines that divide the large square into a grid of nine smaller squares and allow it to be collapsed into a puzzle purse are clearly visible. The practice of decorating puzzle purses as love letters was probably brought to Philadelphia by immigrants from Germany.

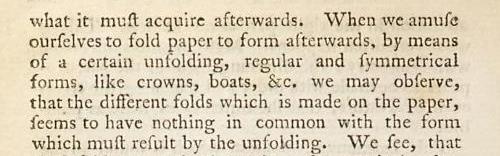

********** K: Paper Crowns Volume IV of 'The Natural History of Animals, Vegetables and Minerals', an English translation, published in London, probably in 1776, of part of the 36 volume work 'Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliére' by George Louis Leclerc, Count de Buffon, contains reference to folding paper crowns, which, from the context, are clearly single-sheet paperfolds not cut or multiple-sheet designs. Unfortunately we cannot tell which particular design of folded paper crown was being referred to here.

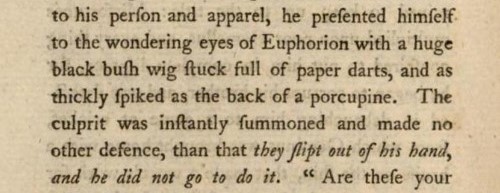

********** The September 1786 issue of 'The European Magazine and London Review' contains a story written by R Cumberland Esq, titled 'The Advantages of Public Education exemplified in the Story of Geminus and Gemellus', which describes paper darts being stuck in a preceptor's wig.

There is no illustration to refer which design of paper dart is being referred to here but comparing and contrasting the description with other similar passages in later books supports the idea that these paper darts are Paper Darts per se. It seems that throwing Paper Darts into schoolmasters wigs was a common occupation for schoolboys at that time. ********** M: Paper Hearts 'Every Lady's Own Fortune-Teller', which was printed for J Roach in London in 1793, contains mention of folding a sheet of paper into a heart. Unfortunately there is nothing to tell us how this was to be done.

********** Cardboard modelling, or cartonnage is a technique for making constructions out of stiff paper or card in which templates are first cut out, then folded up, and finally glued together. The first book about this technique was 'Anweisung zum Modelliren aus Papier oder aus demselben allerley Gegenstände im Kleinen nachzuahmen. Ein nützlicher Zeitvertreib für Kinder' by Heinrich Rockstroh, which was published in 1802. Cardboard modelling has remained a popular pastime ever since.

********** O: Recreational paperfolding designs from doubly or triply blintzed squares Recreational designs developed from doubly or triply blintzed squares of paper begin to appear at the start of the 19th century, the Cocotte in 1801, the Chinese Junk in 1806, and both the Double Boat and the Boat with Sail in 1832. Others such as the Saltcellar, the Jacket and the Trousers, and the Lotus appear at a later date. i. Patenbriefs It has been theorised that these three designs were developed from Patenbriefs (godparent letters and containers for gifts of money) which were commonly folded in a doubly blintzed form in Germany during the 18th century. However, this seems unlikely, since Patenbriefs were not toys but valuable mementos, intended to be carefully kept and referred to for moral instruction, presumably in adolescence. It is more likely that these recreational paperfolds folds were developed from similar blintzed forms used in less formal ways. The only evidence we have, however, for the existence of such 'other forms' is an advertising flyer said to date from the late 18th / early 19th centuries.

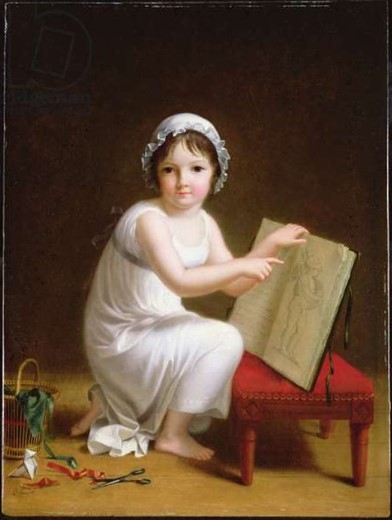

A doubly blintzed Patenbrief from 1763 ********** The most famous, and most folded, design in Western Europe during the 19th century was undoubtedly the Cocotte. It appears in numerous illustrations in books and magazines, on postcards, adverts and in many other forms. It is first evidenced from 1801 from the painting 'Un enfant qui montre les images d’un livre' by Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet-Husson and then from another painting by the same artist in 1806.

'Un enfant qui montre les images d’un livre' by Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet-Husson ********** The Cocotte / Pajarita design is also mentioned in the book 'Jugenderinnerungen eines altes Mannes' (Youth Memoirs of an Old Man), published by Wilhelm Herz Verlag Berlin in 1870, in which Wilhelm von Kügelgen describes how, in about 1812, when the family were living in Dresden, his then tutor, the painter Carl Adolf Senff (1785-1863), taught him, together with his siblings Gerhard and Adelheid, and the Leipzig friends Alfred and Julius Volksmann, to fold Krahen (crows). It is clear from the description that these Krahen were Cocottes / Pajaritas. The children learned to add further folds to develop these crows into Ross und Reiter (Horses and Riders), some of which still survive in museums in Germany.

********** The first explanation of how to fold the design appeared in 'Manuel Complet des Jeux de Société' by Elisabeth Celnart, which was published in 1827. Her description is curiously different to the way in which we would fold the Cocotte / Pajarita today. She says, 'Take a square piece, folded lengthwise in half, then fold over the four corners, like making a dog-ear on the page of a book, so that your paper has a double diagonal or oblique line, and repeat the folds, or rather the small dog-ear corners: repeat this manoeuvre three times. When you fold for the third time pull out one of the dog-ear corners at the longest end, which makes the head of the bird, then the opposite end which forms the tail, then lift the two dog-ear corners on each side, which make the wings.' (Translation courtesy of Edwin Corrie) In simpler modern words, ‘blintz a square three times then pull out the internal paper to create points’. (You can, of course, do the same thing by blintzing a square just twice.)

********** While knowledge of how to fold the Cocotte /Pajarita, and enjoyment of it as a toy, was not limited to the French, it was in France that images featuring Cocottes appeared most regularly. The word ‘cocotte’ can mean a hen or a casserole dish but can also mean a high-class prostitute. It can also, like the Newspaper Hat, which has similarly been absorbed into popular culture, be used as a symbol of childhood or childishness. The design of the Cocotte is usually interpreted as a bird, but it was also often seen as a horse (or perhaps a hobby-horse) and images of people riding Cocottes as though they are horses are common. For instance, this Caricature of Napoleon III by Bertall (1820-1882) was published in the 'Revue comique a l'usage des gens serieux' of December 1848.

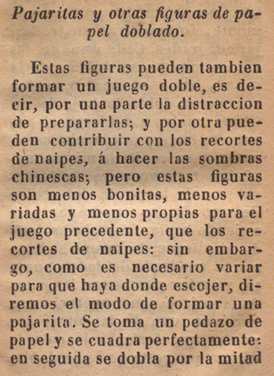

********** In 1847 Elisabeth Celnart's book was translated into Spanish as 'Juegos de los Ninos' in 1847, the section describing the folding sequence being headed 'Pajaritas y otras figuras de papel doblado'.

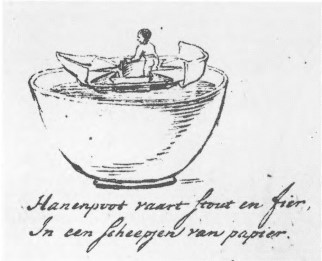

The Pajarita design was subsequently adopted by the Spanish as their own and its origin in France became largely forgotten. Perhaps surprisingly, however, there is no known drawing of a Pajarita from a Spanish illustrator until 1874. ********** iii. The Chinese Junk One of the illustrations in the book 'Hanenpoo' which the Dutch poet Willem Bilderdijk wrote for his young son Julius Willem in around 1807, shows the character Hanenpoot standing in a paper boat which is floating in a bowl of water. This paper boat is clearly a version of the Chinese Junk design, but, unlike almost all other Western drawings of this design, the boat in this drawing has a flat, pointed prow, and so closely resembles the Japanese version of the design. This raises the possibility that the Japanese version of the design had somehow reached the Netherlands and become known to Willem Bilderdijk, though how this could have happened is not clear.

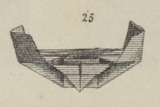

An illustration of the typically Western version of the design, which has two blunt ends, does not appear until the publication of 'De Kleine Papierwerkers 1' by Elise Van Calcar, also in the Netherlands, in 1863.

********** iv. The Double Boat and the Boat with Sail These designs both first appear (along with several cocottes) in a cartonn published in 1832 in the French satirical magazine ‘La Caricature’. It is worth noting that by this date these designs must have been sufficiently well established in French popular culture for them to be instantly recognised and their significance as symbols of childhood understood.

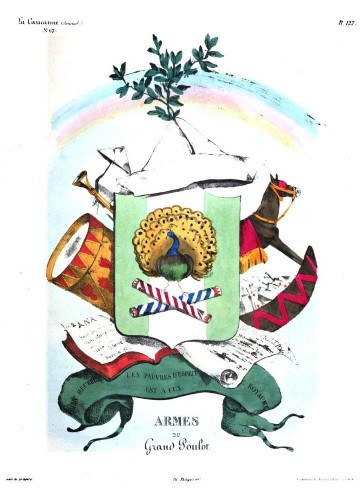

********** The design that, in the UK, is commonly called the Newspaper Hat, first appears in 1832 in a cartoon ‘Armes du Grand Poulot’, which was published in the French satirical magazine 'La Caricature', No 63 of 12 January 1832 (for publishing which the editor of 'La Caricature', Charles Philipon, was sentenced to six months imprisonment and fined 2000 francs). In contrast to the other early paperfolding designs we know of, this design is not folded from a blintzed square but from a rectangle.

********** Q: Recreational paperfolding in books for girls and boys - 1827 to 1851 Recreational paperfolding designs began to appear in books of games and occupations written for both boys and girls during this period, We have already met the earliest of these books, 'Manuel Complet des Jeux de Société' by Elisabeth Celnart, which was published in 1827, and its translation into Spanish, 'Juegos de los Ninos', which was published in 1847. Other books on a similar theme were published in other languages, but notably in English. Many of the 'traditional designs' that we are familiar with today first appeared (or reappeared) in these books. This genre of book continued to appear regularly in several languages in the second half of the nineteenth century and beyond. There is no discontinuity at 1851. ********** i. Write and Fold Games / Draw and Fold Games The 19th century was the heyday of parlour games and some of these involved folding paper. In one particular type of game something was drawn or written on the paper by one person who then folded the paper to conceal what they had written before passing the paper on. The next person then did the same, until everyone taking part had contributed, when the hidden content was exposed, presumably to general hilarity. Two such games, 'L'Histoire' and 'L'Histoire en vers' were explained in Elisabeth Celnart's 1827 'Manuel Complet des Jeux de Société' which we have already met. Another, the game of Consequences, appeared in the 'American Girl's Book or Occupation for Play Hours' by Eliza Leslie, which was published in Boston and New York in 1831. There are many other variations in the literature. ********** The earliest English language book to treat paperfolding as a recreational activity for children was 'The Boy's Own Book' by William Clarke, which was published in London in 1828 and in New York in 1829. According to Robert William Henderson writing in his 'Ball, Bat, and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games', published by the University of Illinois Press in 2001, ’It was a tremendous contrast to the juvenile books of the period, which emphasized piety, morals and instruction of mind and soul; it must have been received with whoops of delight by the youngsters of both countries.’ The paperfolding content consisted of a description of the Paper Furnace effect (where a lead bullet wrapped in paper can be melted without the paper catching fire), Troublewit, the Buddha Papers, the Cherries Puzzle, and another variation of the Cherries Puzzle called the Card Puzzle. Of particular interest is mention of 'a blind young man ... who may be often seen about the streets of London' who turns the paper (ie Troublewit) into 'the likenesses of a great number of things, animate as well as inanimate' although 'they are, we must confess, but rude resemblances'.

The 1829 edition of this work was translated into French and published as 'Manuel des Jeunes Gens' in 1931. ********** iii. The Girl's Own Book, 1833 'The Girl's Own Book' by Lydia Marie Child. which was published in New York in 1833 contains instructions for folding 'Paper Ball Baskets' (baskets made of card and decorated using the quilling technique), 'Paper Rosette Baskets' (baskets made by combining Froebel Stars, which appear here in the historical record for the first time), 'Alumets' (ornamental paper spills), a way to make a circular paper screen (or pleated paper fan) and several fold and cut effects including the 'Three Crosses' (a version of the Fold and Cut Latin Cross effect). The same book also contains the following interesting passage: 'Folded Papers. There are a variety of things made for the amusement of small children by cutting and folding paper; such as boats, soldiers' hats, birds, chairs, tables, baskets, &c. but they are very difficult to describe; and any little girl who wishes to make them, can learn of some obliging friend in a very few moments.' ********** iv. The School Boy's Holiday Companion, 1840 The first book to contain diagrams for some of these less familiar designs was 'The School Boy's Holiday Companion' by Thomas Kentish, which was published in 1840. It is the earliest source of diagrams for the Paper Banger and the Bellows. This book also contains diagrams for the 'Catherine of Cleves Box' (the first appearance of this design since 1440) and for the Paper Boat (the first appearance of this design since 1498 - if we accept the early reference as being intended to represent this design - otherwise the first appearance ever). ********** v. The Boy's Holyday Book, c1842 'The Boy's Holyday Book' was published by G H Davidson in London sometime between 1842 and 1844 The second edition is dated 1845. Among other things it contains an explanation of how to make kite tails from folded paper. ********** R: Friedrich Foebel and the Kindergarten Friedrich Froebel, born 1782 and died 1852, was an educationalist from Thuringia, now part of Germany, who developed a theory of education through both self-directed and teacher directed play and founded what became known as the Kindergarten (Children's Garden) movement. He created a system of five 'gifts', objects with which children could play, and by playing, learn. He later extended the system, perhaps in around 1850, to include 'occupations', or as we would probably call them, activities, which would function in the same way. Paperfolding formed the basis of three of these occupations, 'Falten' (paperfolding per se), 'Ausschneiden und Aufkleben' (Cutting Out and Mounting) in which the paper is first folded, then cut, then opened out and finally mounted on another sheet of paper or board to create a pattern, and 'Verschnuren' (Interlacing) in which flat geometric figures are created by folding and interweaving one or more paper strips.and, to some small extent also played a part in a fourth, 'Flechten' (weaving).. Froebel opened his first school for young children at Bad Blankenburg in Thuringia in 1837. It was originally named 'The Play and Activity Institute' but was renamed 'The Kindergarten' in 1840. By 1848 there were 31 kindergartens in German states, almost all in Protestant areas. In 1851 the Prussian government suppressed kindergarten education in Prussia and other German states followed suit. Froebel went to live at Marienthal, where he died on 21 June 1852. ********** S: The Paperfolding Occupations of Friedrich Froebel This section gives a brief summary of the nature of each of Froebel's paperfoldng occupations. The only information we have about the original nature of these occupations comes from the writings of some of his followers. We have no direct evidence from Froebel's own writings. It seems likely that the occupations of Flechten, Ausschneiden und Aufkleben and Verschnüren were largely, or perhaps entirely, invented by Froebel himself, and this is also probably true of the folding of Erkenntnisformen (Learning Forms) and Schönheitsformen (Forms of Beauty) The extent to which he was responsible for originating the folded Lebensformen (Forms of Life) is more difficult to determine. i. Flechten In this occupation a frame is created by first folding a sheet of paper in half, cutting parallel slits into the folded edge to divide it into strips and then opening it out again. These upright strips are not loose but stay connected to the outside of the frame at both top and bottom. Other, completely loose, strips are woven across the frame, going under and over the upright strips, to create patterns. Beyond the making of the frame, and the fact that both the frame and the strips need to be flexible (ie foldable) to allow the weaving to take place, there is no substantive paperfolding content to this occupation.

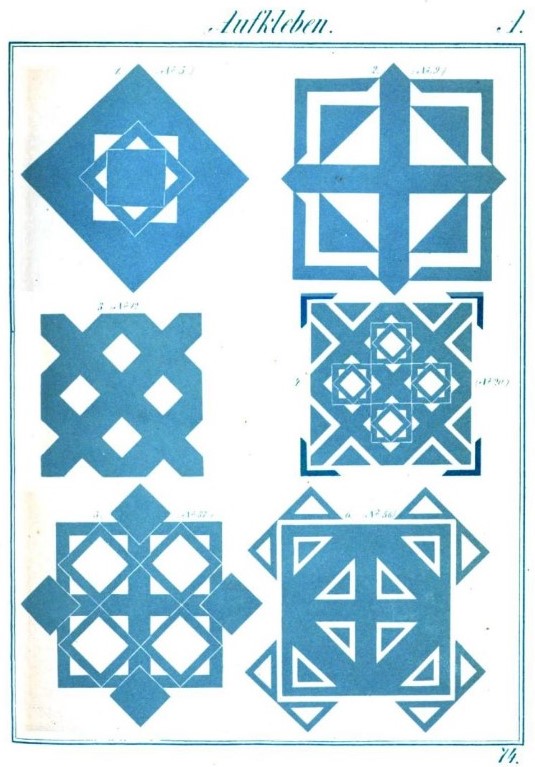

********** ii. Ausschneiden und Aufkleben In the occupation of Ausschneiden und Aufkleben (Cutting Out and Sticking On), a square of paper is first folded into an eight-layer right angle isosceles triangle before parts of the triangle are cut away. The paper is unfolded back to the square, then mounted on card or another piece of paper to create a decoration. The parts cut away are then also unfolded and added to the decoration in a symmetric way (the principle being that no part of the paper should be wasted).

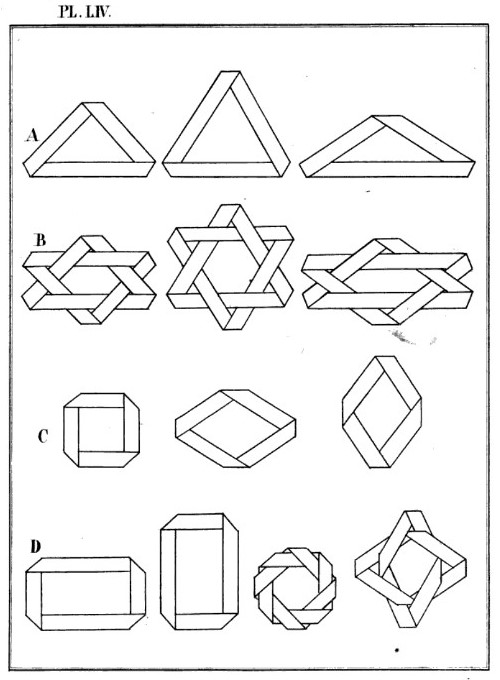

********** iii. Verschnüren Verschnüren (Interlacing): In this occupation flat geometric figures are created by folding and interweaving one, or several, paper strips.

A plate from 'Manuel pratique des jardins d'enfants de Frédéric Froebel', by J F Jacobs, published in 1859. ********** iv. Falten The Falten occupation was divided into three parts, the folding of Erkenntnisformen (Learning Forms of Forms of Knowledge), Schönheitsformen (Forms of Beauty) and Lebensformen (Forms of Life). The distinction between Learning Forms, Forms of Beauty and Forms of Life was not only applied to the Falten occupation, but also to the designs children could produce using other occupations and gifts. In Froebel's original scheme, all of these forms were folded from squares, a choice of starting shape that has influenced recreational paperfolding ever since. The only piece of writing of Froebel's dealing with paperfolding that we have is a fragment found in 'Friedrich Froebel's Gesammelte padogogische schriften' (Friedrich Froebel's Collected Educational Writings) edited by Wichard Lange, which was published in 1861 (although the Fragment must date to or before 1852, the year Froebel died). This fragment includes a description of Froebel's method of cutting four squares from a rectangle (leaving a central strip which can be further divided into smaller strips to use in the occupation of Verschnuren).

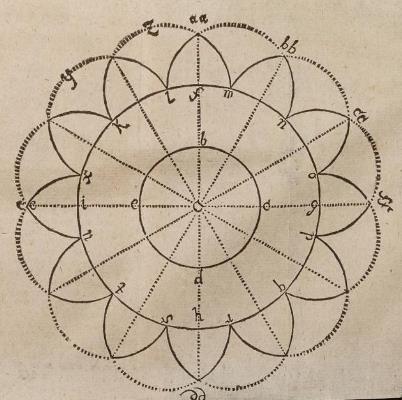

Illustration from 'Das Paradies der Kindheit' by Lina Morgenstern, which was published in Leipzig in 1861. ********** v. Erkenntnisformen (Learning Forms) In the case of the Learning Forms we are fortunate to have a fragment of Froebel’s own writings which explains his approach. This appeared in 'Friedrich Froebel's Gesammelte padogogische schriften' (Friedrich Froebel's Collected Educational Writings) edited by Wichard Lange, which was published in two parts in 1861. It sets out a way to fold and cut a square from an irregular piece of paper, explains how to fold the square in a few basic ways and how making and studying these folds reveals some basic mathematical principles. We do not, unfortunately, have any similar writings from Froebel himself about either his Forms of Beauty or Forms of Life, and information about this has to be gathered, and often inferred, from the manuals written by his followers. ********** vi. Schönheitsformen (Forms of Beauty) Forms of Beauty are essentially flat patterns which are not only folded from squares but are also themselves square in shape and are therefore easy to glue in groups into albums or exercise books. The simpler ones are generally folded from Froebel's first groundform (the singly blintzed square) and the more advanced ones from his second groundform (the doubly blintzed square).

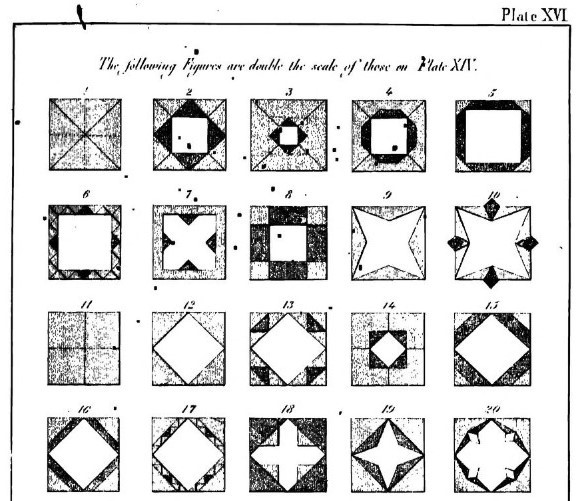

Album containing Forms of Beauty folded by Fannie E Kacline c 1890 in the collection of MOMA, Mew York ********** As with all the other categories of Froebelian paperfolding it is difficult to know which designs originated with Froebel himself, and which were invented by his followers. However, Mary Gurney, writing in her book 'Kindergarten Practice', which was published around 1877, states that designs 1-20 in Plate XVI (see below) are 'attributable to Froebel'. These are all developed from the second grounform.

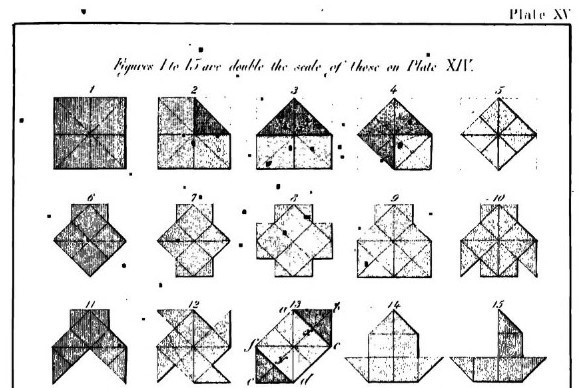

********** vii. Lebensformen (Forms of Life) Forms of Life are geometric paperfolds which are interpreted as everyday objects. It appears that In Froebel's original scheme these were developed from his second and thrd groundforms (the doubly and triply blintzed square). His followers also developed simple Forms of Life from the first groundform (the singly blintzed square) and other basic folds. In her 'Kindergarten Practice', which was published around 1877, Mary Gurney states that the designs numbered 1-15 in Plate XV (see below) are 'attributable to Froebel'.

These comprise, A Jar (The Scent Bottle), A Jacket with Short Sleeves (The Muff), A Green Cross (The Cross), Inkstand (The Inkwell), A Jacket with Sleeves (The Jacket), Children's Trousers (The Trousers), Windmill, Cigar Case, Ship and Sailing Boat (The Boat with Sail). She also mentions that the Windmill can be converted to a Table, and the Sailing Boat to a Twin Boat (The Double Boat). We know that the Cross, the Boat with Sail and the Double Boat were not invented by Froebel, and the same may apply to the other designs as well, but this is at least good evidence that these designs were included in the original Forms of Life repertoire. There is an interesting passage about Folds of Life in 'Reminiscences of Friedrich Froebel' by Baroness B von Marenholtz-Bulow, which was published in 1877.

********** T: Other Educators and Paperfolding It is worth noting that Froebel was not the only educator of this period who was interested in paperfolding. i. Christian Gotthilf Salzmann 'Ameisenbüchlein oder Amweisung vernunftigen Erziehung der Erzieher' (Ant Book or Instruction for the Reasonable Education of Educators) by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann was published in Leipzig in 1806. It contains two passages which evidence that paper was being folded 'to make various figures' and used for 'making all kinds of toys' at this date. ********** ii. Samuel Wilderspin In his influential book 'Infant Education', which was first published in 1823, Samuel Wilderspin mentions demonstrating how to fold paper 'into a variety of forms' and then how he failed to fold it into the form of a paper boat, having forgotten the folding method. ********** iii. Martin Chatelain In 1849 the French publication 'Bulletin de la Societe D'Encouragement Pour L'Industrie Nationale' published a report by the mathematician Theodore Olivier, titled 'Enseignement Industriel - Geometrie Pratique', which explained a new method, discovered by Martin Chatelain, of teaching practical geometry using paperfolding. The report recommends its use in the teaching of apprentices. Full details of the method are, unfortunately, not given. ********** |

|||||||