| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 7/8/2023 x |

|||||||

| A Brief History of Educational and Recreational Paperfolding in Japan after Cross-Fertilisation | |||||||

| Up

until 1875 the paperfolding traditions

of Japan and Europe were, as far as we know, entirely

separate, and those few instances where similar or

identical designs existed in both traditions, notably the

Takarabune / Chinese Junk, the Paper Boat, the Thread

Container / Puzzle Purse are most probably the result of

independent parallel creation. We cannot completely

discount the possibility that there may have been some

cross-fertilisation between the two traditions in the

period between 1543 and 1639, when Western traders and

missionaries were largely welcomed in Japan, but there is

no specific evidence to show that this occurred. The following external sources have been relied on for information in writing this section: (1) 'History of Origami in the East and the West before Interfusion' by Koshiro Hatori, published in 'Origami 5: Fifth International Meeting of Origami, Science, Mathematics and Education'. (2) 'Missionary Froebelians' Pedagogy and Practice: Annie L Howe and her Glory Kindergarten Teacher Training School' by Yukio Nishida, published online by Cambridge University Press on 7th April 2022. (3) 'The Black Forest in a Bamboo Garden: Missionary Kindergartens in Japan, 1868-1912' by Roberta Wollons, published in History of Education Quarterly , Spring, 1993, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 1-35 ********** A: Translations of Kindergarten manuals In the early Meiji period, from 1868 onwards the Japanese government became interested in Western-style kindergarten education, and in around 1871, Shinzo Seki, a teacher of English at the Tokyo Women’s Normal School (a Normal School is a teacher training institute), translated several Western kindergarten manuals into Japanese. Among these were 'The Kindergarten' by Adolf Douai and 'Moral Culture of Infancy and Kindergarten Guide' by Mrs Horace Mann and Elizabeth P Peabody (3) (although I do not know whether the latter was a translation of the first or second editions). Both of these books make some mention of paperfolding but neither place much emphasis upon it, or give any illustrations of folding methods or finished folds. (Two other Froebelian books, 'A Practical Guide to the English Kinder Garten' by Joh and Bertha Ronge, published in 1855, and 'Der Kindergarten' by Hermann Goldammer, published in 1869, are also said to have been influential in early kindergarten education in Japan, but I do not know if they were similarly translated into Japanese, and, if so, when and by whom.) ********** B: The first Japanese kindergarten The first Japanese kindergarten was established in 1875, attached to the Yanaike Elementary school in Kyoto. This was a private rather than a public school. (I have not managed to find out any information about the curriculum at this kindergarten, whether it included paperfolding or not, or how long it remained open.) The first public (ie state sponsored) kindergarten opened in the following year, 1876, attached to the Tokyo Women’s Normal School. The 'superintendent' of this kindergarten was Shinzo Seki and the 'head teacher' was Clara Zitelmann Matsuno. Clara was married to Hazama Matsuno, who was an official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Clara had met Hazama while he was accompanying Prince Kitashirakawanomiya on his studies in Europe. There is some difference of opinion about whether or not Clara was a fully qualified kindergarten teacher, although it seems that she had received at least some training at the Froebel Institute in Germany. This kindergarten was renowned for sticking closely to the use of the original Gifts and Occupations and so it is likely, although not specifically evidenced, that from the beginning Clara Matsuno would have included the three Froebelian paperfolding occupations of falten (paperfolding), verschnuren (interlacing), and ausschneiden und aufkleben (cutting out and mounting) in her syllabus. As a consequence, the Western European tradition began to become known in Japan, and to affect Japanese recreational paperfolding design and practice.

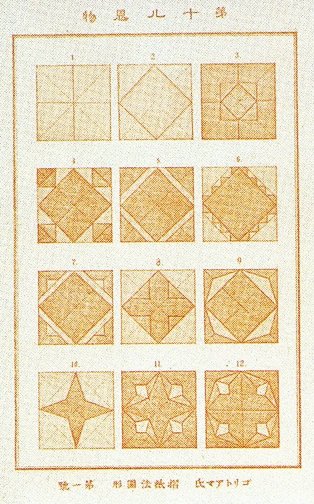

This print shows Clara Matsuno and her trainee teachers, Fuyu Toyoda and Hama Kondo, playing the Pigeon's Nest game with Kindergarten children. ********** C: The Japanisation of the kindergarten syllabus The earliest specific evidence for the use of paperfolding within the curriculum of the Tokyo Women's Normal School Kindergarten comes from 'Yochien Ombutsu No Zu' (Illustrations of Kindergarten Gifts) which was published by the School in 1878. (I have not seen the text of this work, just some those of the illustrations that relate to paperfolding. There are several pages dedicated to Forms of Beauty (part of the Falten occupation). These illustrations have been redrawn from illustrations in the 1874 edition of 'Der Kindergarten' by Hermann Goldammer.

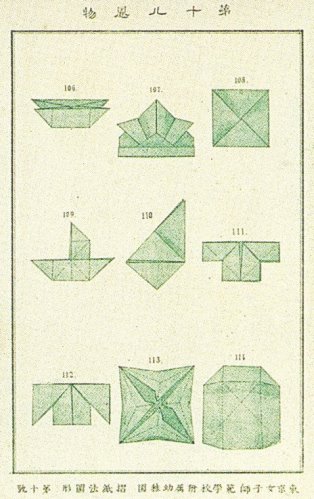

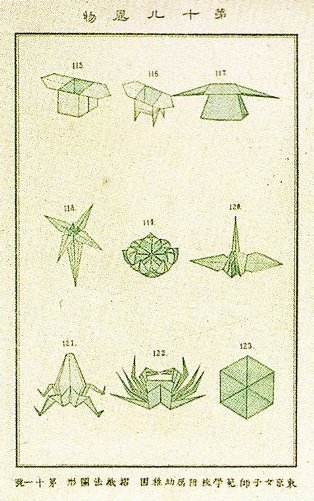

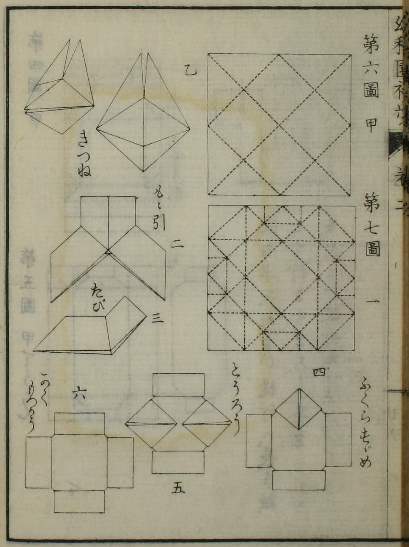

Specimen page illustrating Forms of Beauty from the 'Yochien Ombutsu No Yu' ********** There are also several pages picturing what in the Froebelian tradition would have been called Forms of Life (another part of the Falten occupation). These illustrations show that even in the brief period of 2 years since this kindergarten had opened a process of Japanisation (often referred to as ethnicisation when it affects more than one country) was underway. While the book includes some of the familiar Western-style kindergarten paperfolds (the Cigar Case, the Cup and Saucer (turned upside down and re-imagined as a house), the Cross, the Pair of Boots, the Cocotte, the Jacket, the Trousers, the Newspaper Hat, the Double Boat, the Boat with Sail, the Shirt, the Steamship (also turned upside down, although I do not know what it was re-imagined as), and the Lotus), it also includes several previously unknown designs developed from the basic Froebelian groundforms (the Fox Face, the Kikuzara, and the Winnowing Box). This is, of course,consistent with the Froebelian principle that the occupations should be used creatively, rather than simply reproduced in a sterile manner. The fact that two of the designs are pictured upside down almost certainly also means that the meaning of the designs have been re-interpreted in a way more consistent with Japanese culture. The surprise is that these pages also include some entirely Japanese designs (the Pinwheel / Thread Container, the Kabuto, the Sanbo, the Sanbo on Legs, the Kago, the Lily, the Paper Crane, the Blow-up Frog, the Crab, the Hexagonal Incense Packet and the various Japanese figures), which bear no relationship whatsoever to the Froebelian groundforms, and some of which would seem far too complicated to be reproduced by kindergarten pupils. This suggests that already at this early stage there was a desire to make kindergarten education in Japan uniquely Japanese, with the probably unintended consequence that the benefits of Froebelian style kindergarten education were, eventually, largely lost.

Specimen pages illustrating Forms of Life from the 'Yochien Ombutsu No Yu' ********** There is no evidence from this publication (or indeed from anywhere else) of the use in Japanese kindergartens of the very simple Folds of Life (simpler than a singly blintzed square) that are found in some European Froebelian manuals. There is also no evidence from this publication for the use of Forms of Knowledge, the third, and arguably educationally most important, element of the Falten occupation, which were used to teach mathematical principles within the kindergarten, but this may just be because they were outside the purview of the 'Yochien Ombutsu No Zu' publication. ********** Shinzo Seki's 'Yochien Ho Niju Yuki' (Twenty Joys of Play in Kindergarten) was published a year later in 1879 and contains drawings of children sitting at tables engaged in various kindergarten occupations. The illustration relating to the occupation of paperfolding shows a Paper Crane, a Noshi and what appears to be a windmill base with the front flaps folded in half outwards (which is possibly a Hanabishi). All of these designs are of Japanese, not Western European origin.

********** There is also an illustration relating to the occupation of Verschnuren (interlacing), which, as far as I know, is the only evidence for the use of this occupation in the kindergarten in Japan.

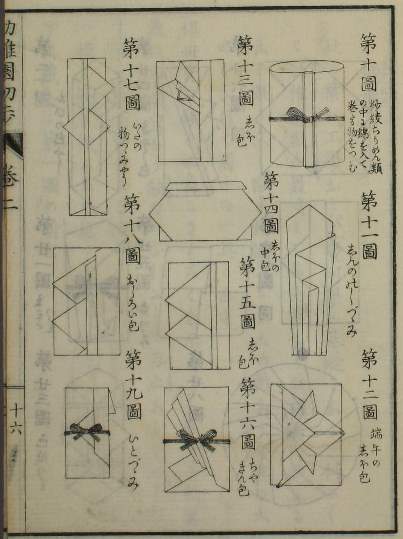

********** The trend towards the Japanisation of kindergarten paperfolding activities is further evidenced in 'Kindergarten Shoho' (Preliminary Kindergarten) by Iijima Hanjuro, which was published in 1885. Once again the section relating to paperfolding per se includes a mixture of Western European and Japanese designs, some of which are Forms of Life but others of which are traditional tsutsumi (wrappers). Many of these forms, of both kinds, are quite complex to fold. There are no illustrations of Forms of Beauty in this book.

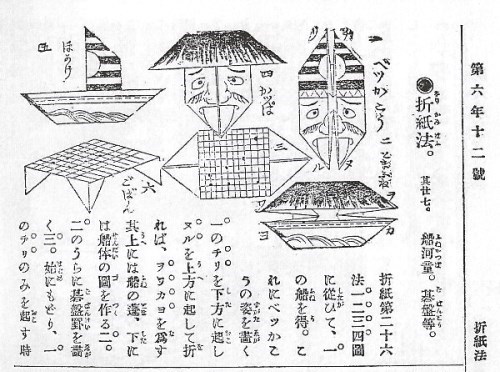

A page of Forms of Life from 'Kindergarten Shoho' **********

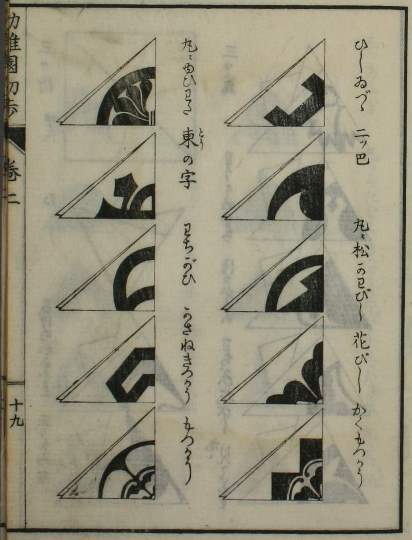

A page of wrappers from 'Kindergarten Shoho' ********** 'Kindergarten Shoho' also contains a number of pages explaining how to cut out symmetrical designs for Japanese family crests or mon, a traditional Japanese activity for children which, in another clear instance of Japanisation, appears to have replaced the Froebelian occupation of Ausschneiden und Aufkleben (Cutting Out and Mounting) within the kindergarten curriculum.

A page of fold and cut family crest designs from 'Kindergarten Shoho' Incidentally, the word 'origami' was first used to mean 'recreational paperfolding' in this book. ********** D: The Influence of the kindergarten on paperfolding in Japan It is easy to assume that knowledge of European-style folds based on Froebel's second and third groundforms, whether imported from Europe or newly invented in Japan, would have been spread rapidly throughout Japan as a result of being included in the kindergarten curriculum, but this is not necessarily the case. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, despite the government's wishes, kindergarten-style education of 3 to 6 year olds did not in fact spread very quickly throughout Japan. It was not a complulsory part of the educational system (and there was, at first also another system of primary education running alongside it.) In addition kindergartens charged fees, and, of course, not all families could, or were willing to, afford these. Only three public kindergartens, for instance, were opened in 1879, and only more one public kindergarten and two private kindergartens were opened in 1880. Even by 1906 there were only 360 kindergartens in Japan, and between them they were educating only 1.4% of 5-year-olds. Secondly, even where kindergartens were established, paperfolding was not necessarily a significant part of the curriculum. In 1889, in Kobe, the Glory Kindergarten and its attached teacher training school were opened by Annie L. Howe, who had been sent to Japan by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions of the Congregational Church. Howe was an experienced kindergarten teacher, who had graduated from the kindergarten training school run by Mrs. Alice Putnam in Chicago and had already taught for 9 years as a kindergarten teacher in the United States. Howe was critical of the emphasis on the gifts and occupations in Japanese kindergartens and preferred to stress other activities such as the care of plants and animals, story telling, singing and play. The Glory Kindergarten Training School was influential in providing teachers for many other kindergartens but its core curriculum did not include any instruction on the use of Froebel's gifts or occupations, of which, of course, paperfolding was one. Equally it would be easy to assume that recreational paperfolding was to some extent universal in Japanese society and that grandmothers and mothers taught paperfolds to their children who in turn handed them down to their own. I think there can be no doubt that this happened, but to what extent? By the very nature of this process it leaves very little trace in the historical record. The paperfolding design which appears most often in Japanese prints of all periods is the Paper Crane, followed by the Paper Boat and some of the other members of the Classic Ten. Very few other designs appear in any prints at all. ********** E: Kuzuhara Koto Information aboout this topic will be added here shortly. ********** F: Designs in Japanese Children's Magazines Fortunately, from 1893 onwards, two childrens' magazines, 'Yonen Zasshi' and ' Shokokumin' began to publish origami designs in their pages, and this provides us with an excellent snapshot of what type of designs were being folded at this time. 'Yonen Zasshi' published six such articles in 1893 and two more in 1894. 'Shokokumin' published many more, between 1893 and 1896. In the first issue of 1894, the editor of 'Shokokumin' , seemingly rather proudly, wrote: 'Since old days of this country, it seems there have been no examples that collect this many origami methods. We still have ten more contributions here and will publish them in later issues and expand our collection.' All the articles in 'Shokokumin' seem to have been contributed by readers (and this may well be the case with 'Yonen Zasshi' as well). These readers came from all over Japan, evidencing that the folding of origami designs was widespread at this time (although this does not, of course, tell us what proportion of the population regularly or sporadically folded origami designs, something that would be extrememly helpful to know). The most striking aspect of these articles is the sheer variety of the designs they feature. There are some from the Western paperfolding tradition (the Waterbomb, the Steamship, the Lotus) and others that are already well known from Japan (the Long Lantern, the Lily, the Cicada), and some that are new (the 'Minogame' (ancient turtle) and the Simple Fukusuke). There are also a number of Connected Cranes designs (the only evidence we have so far that folding in the style of the Senbazuru Orikata continued during this period), a cut and glued modular design (the Hexagonal Tematebako), two simple packages / wrappers, a transformable picture sequence, and even three cardboard modelling type designs. This is clear evidence that the older forms are being remembered and that new forms are being devised and re-interpreted alongside them at this time.

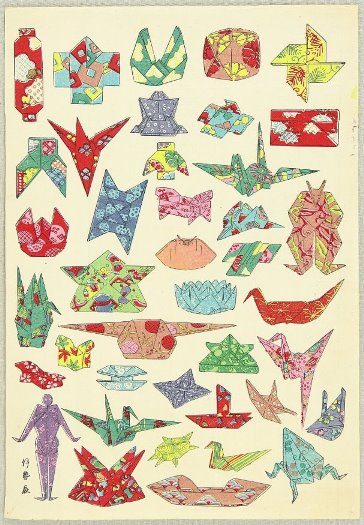

A transformable picture sequence from 'Shokokumin' issue 12 of 1894 ********** G: Designs in a monozukushi-e print Many of the designs which appear in these magazines can also be seen in this monozukushi-e print (by an unknown artist), which, probably, dates to the late Meiji period ie to sometime before 1812.

********** H: Paperfolding in elementary schools In 1886 'handicrafts', including paperfolding, was introduced into the curriculum of both lower and higher elementary schools as an additional (ie optional) subject. In a revision of this ordinance in 1900 it was stipulated that 'the purpose of handicrafts' is 'to provide the ability to manufacture simple goods and to cultivate a habit that favors working'. As a result of this inclusion of handicrafts in the elementary school curriculum, sections on paperfolding began to appear in school textbooks. The earliest manual that includes paperfolding that I have been able to find, is 'Jinjo Kouto Shogaku Shuko Seisakuzu' (Handicrafts for ordinary higher elementary schools) by Hideyoshi Okayama, which was published in 1903. Thereafter, similar manuals continued to be published until at least 1935. Handicrafts went from being an optional to a compulsory subject in upper elementary schools in 1926 and in ordinary elementary schools in 1927. The range of designs featured in these manuals is not extensive. The same designs appear over and over again, though not all the designs appear in all the manuals. It is perhaps fair to say that some kind of paperfolding 'canon' seems to have become established during this period (and possibly before). This 'canon' includes some designs that are either originally Western, or are derivations of originally Western designs, but the majority of the designs appear to be of Japanese origin (athough, in many cases, it is difficult to know whether they are of ancient or recent invention). It seems likely that paperfolding in elementary schools was much more important in the development of paperfolding in Japan than paperfolding in kindergartens.

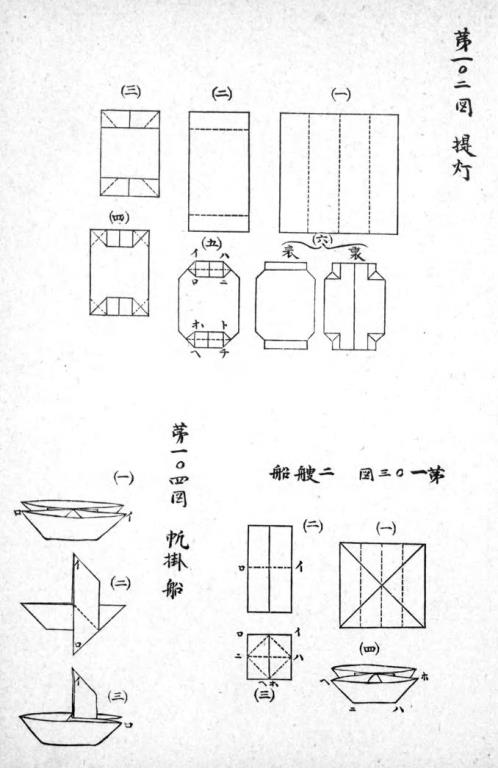

A specimen page from 'Jinjo Kouto Shogaku Shuko Seisakuzu' ********** I: The Frederick Starr Article In October 1922 the English language tourist magazine 'Japan' published an article written by Frederick Starr, an American anthropologist, titled 'The Art of Paper Folding in Japan' which provides an interesting snapshot of paperfolding in Japan at that time . Starr writes about, and lists, a box of 24 paperfolds folded for him by a seven year old girl, many of which are identifiable as familiar paperfolds from the kindergarten tradition. He also mentions the folding of tsutsumi, ocho and mecho, a book called 'Shikaka origami dzukai' (which I have been unable to trace) and another called 'Shinkufu mon kata kiriyo' about the folding and cutting of mon (similarly). Starr also explains how he was shown, and allowed to have copied, the Kan No Mado ms. The ms itself, however, was not published at this time. ********** J: Origami Moyo 'Origami Moyo' is a two volume set of woodprints by Kawarazaki Kodo, mostly featuring origami designs, which was published in 1935. It contains drawings of several designs that are not previously known from any other source, suggesting that the process of paperfolding design innovation was ongoing during this period. Many of the prints also feature plants and flowers that are made by combining a number of very simple folded leaves or petals to create the finished design. It is not clear whether or not any of the designs featured in these books were Kawarazaki Kodo's own.

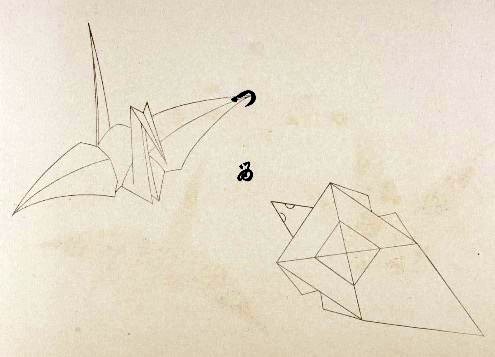

The title page for print 1 features the Paper Crane and Minogame (a turtle trailing seaweed) ***

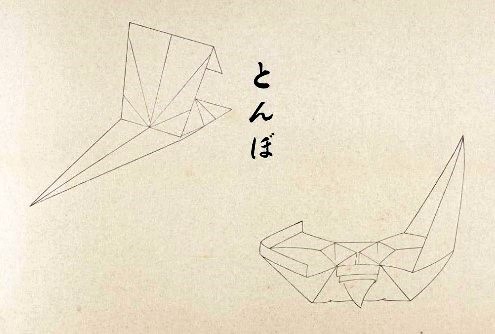

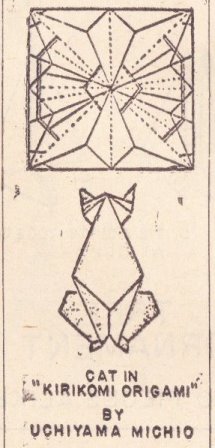

The title page for print 14 of Volume 1 features the Takarabune and a previously unknown boat with sail. ********** K: The new breed of paperfolders Up until the early 1930s, it is, I think, true to say that we do not know the name of the original designer of any specific paperfolding design (which is why, of course, they are considered to be 'traditional'). From the early 1930s onwards, however, that situation changes and we begin to see a situation developing that is much more like the modern origami culture where some few paperfolders publish books containing, at least mostly, their own designs. i. Michio Uchiyama (1878 to 1967) Michio Uchiyama developed a heavily cut style of paperfolding, known as 'kirikomi' or 'koko' origami. To Michio Uchiyama cutting slits into the starting shape of the paper was a good thing because it made the designs more efficient. Paper that would otherwise have been hidden, or, in his terms, wasted, inside the design could be brought out and used to create more realistic details. In 1933 he published 'Origami Kyohon' the first of his many books on paperfolding.

Illustration taken from an article by Toshie Takahama in 'The Origamian' Vol 7: Issue 3 of Winter 1967 ********** ii. Isao Honda (1888 to 1976) In 1908, Isao Honda, who was subsequently to become a prolific author of books about paperfolding, travelled to Europe to study painting, which he did in both London and Paris. Sometime later, after his return to Japan, he wrote his seminal work 'Origami', which was published in two parts, an 'upper' part, usually known as 'Part One', which was published in 1931, and a 'lower' part, usually known as 'Part Two’, published in 1932. Full details of the contents of Part Two have not yet become known in the West. Part One contains diagrams for 81 designs in all. Some of these are designs had previously appeared in other Japanese books, including the kindergarten manuals, or magazines, some are European napkin-folds, while others are completely new. Because of the time Isao Honda had spent in Europe, we cannot be entirely certain whether these previously unknown designs originate from the Japanese or European traditions, or, indeed, are of Isao Honda’s own invention.

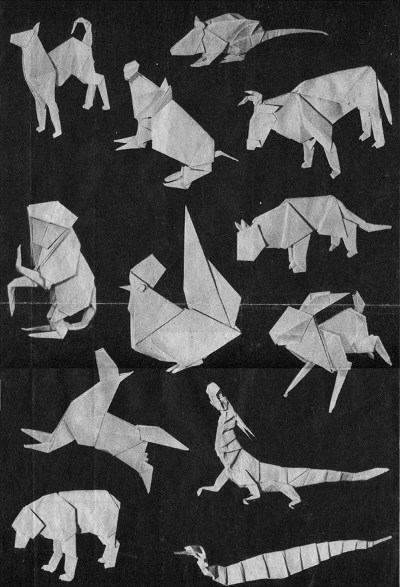

A page from 'Origami Part One' In 1944, during the Second World War, Honda published 'Origami Shuko' which contained material from both his previous books, some designs by Akira Yoshizawa, which are specifically and clearly attributed to him, and some other new material, which may have been newly collected traditional designs or designs invented by Honda himself. The most interesting aspect of this new material is the inclusion of several compound glued designs for animals and birds, usually folded in two parts which, are then glued together. These include Honda's Peacock. Only one of these designs, a camel, is attributed to Yoshizawa. There is no direct claim within the work that Honda is the originator of these designs. However, he did claims that these designs were his own, and that in fact he originated the two-part compound glued technique, in his later work 'The World of Origami'. It should also be noted that Yoshizawa seems to have disputed this claim. ********** iii. Taneji Nakajima Taneji Nakajima us the invisible man of Japanese paperfolding. We know virtually nothing about him, but between 1932 and 1952 he published a series of books of his own original designs. He frequently used cuts to add more realistic detail to the basic design. His designs were intended to be decorated after they had been folded. ********** iv. Akira Yoshizawa (1911 to 2005) At some time, probably after the publication of 'Origami', Isao Honda made the aquaintance of a much younger paperfolder, Akira Yoshizawa. We know very little about the true nature of their relationship, which was acrimonious in later years, but must have been reasonably friendly in the early days, because in 1944 Honda included a number of Yoshizawa's original designs in his book 'Origami Shuko'. Many of these designs were made from equilateral triangles and other less usual paper shapes, which Honda clearly thinks a worthwhile innnovation. At this time Yoshizawa was otherwise largely unknown. He did not begin to become nationally famous until January 1952 when an article about his origami design work was published in the magazine 'Asahi Graf', which in turn led to publication of a series of articles in 'Fujin Koron' (Ladies’ Opinion) magazine in April to December of the same year.

Yoshizawa's zodiac designs as published in Asahi Graf on January 9th 1952 (From the Gershon Legman archives at Museo del Origami in Colonia, Uruguay) Yoshizawa's first book, 'Atari Origami Geijuitsu' (The Art of Origami) was published in 1954. According to the paperfolding historian David Lister, in his introduction, Yoshizawa wrote that 'he had avoided the use of scissors because he did not want to transgress beyond the field of 'paper folding'', which was a stark contrast to the approach of Michio Uchiyama and perhaps set Yoshizawa apart from many other paperfolders of his day. According to information in the book 'Akira Yoshizawa: Japan's Greatest Origami Master' published by Tuttle in 2016, Yoshizawa established a paperfolding society, rather grandly called the 'International Origami Study Society', in 1954. In 1957, Yoshizawa's second book 'Origami Dokuhon' (Origami Reader) was published. This book was subtitled 'From play to creation' and was aimed at Mothers and Teachers. It is in two parts. The first part contains simple designs suitable for young children. The second part explains Yoshizawa's design philosophy of creative origami and shows how various types of more advanced designs can be produced and adapted. It included some of his most famous designs, including his Nun and his Butterfly, and demonstrated a growing mastery of form using many different paperfolding techniques. However, Yoshizawa does not say whether any particular design is traduitional, his own, or borrowed from another paperfolder. (Honda's Peacock is included without attribution, for instance.) This book was quite influential internationally, since by this time, as a result of a correspondence with the American write Gershon Legman, Yoshizawa's skill at origami design had become known to a group of paperfolding aficionados in the West, but it is unclear how much influence it had in Japan itself. ********** v. Kosho Uchiyama (1912 to 1998) Kosho Uchiyama was the son of Michio Uchiyama. In 1938 he became a Buddhist priest. He is nowadays much more famous for hiswritings about Buddhism than for his writings about origami, but this was not always the case. His first book 'Yoku Wakaru Origami' (Easy to Understand Origami) was published in 1956 and was followed by 'Origami Zukan' in 1958 and his opus magnum, just titled 'Origami', in 1962. According to 'A Paperfolder's Trip to Japan' by Florence Temko, which was published in Vol 4: Issue 2 of 'The Origamian' for Summer 1964, and which describes her meeting with Kosho Uchiyama, 'Mr Uchiyama volunteered the information that although he used cuts in the past he is now able to achieve the results he looks for without cutting.' ********** vi. Toyoaki Kawai (1932 to 2007) Toyoaki Kawai was once a pupil of Yoshizawa but broke away from his organisation and became an author and teacher of origami in his own right, inventing many of his own original designs. Vol 4: Issue 2 of 'The Origamian' for Summer 1964 contains a report of 'A Paperfolder's Trip to Japan' by Florence Temko which records that Toyoaki Kawai 'maintains the Origami Design Room' and directs 'the Society for the Study of Creative Origami.' The first of his books, 'Origami Shu' (Origami Play), was published in 1965. In the Summer of that same year Kawai visited the World's Fair in New York and also visited Los Angeles, bringing a party of other Japanese folders, including Toshie Takahama, with him.

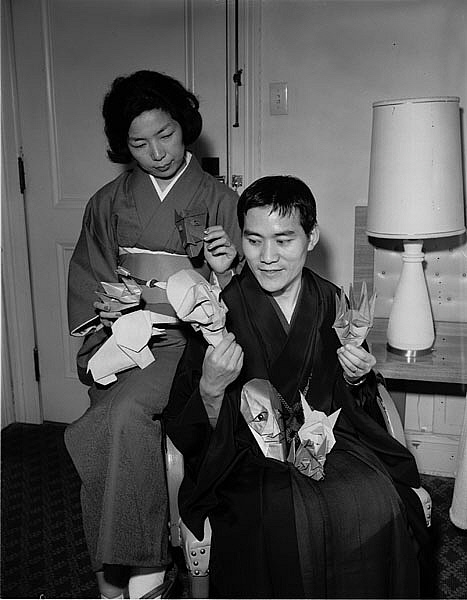

This photograph of Kawai and wife, Atsuko, holding some of the masks for which he was famous, was taken in Los Angeles in May 1965 ********** vii. Kunihiko Kasahara (born 1941) Like Kawai, Kunihiko Kasahara was also a pupil of Yoshizawa. Like Kawai he also eventually branched out on his own, but as far as I know he never took formal pupils himself or founded his own origami society in the way that Yoshizawa and Kawai both did. Kunihiko Kasaharawas a prolific creator of original designs and soon became an equally prolific author of books about origami. His first book, 'Haha to ko no origami no hon' (Origami for Mother's and Children), was published in 1965 and was quickly followed in 1966 by publication of 'Omoide No Origami' (Origami in Sweet Memory) and 'Origami O Tanoshimu Hon' (Origami to Please Everybody). ********** In November 1954 an eleven year old Japanese girl from Hiroshima, called Sadako Sasaki, who had been just two at the time the USA had dropped an atomic bomb on that city in 1945, but who had survived because her family lived sufficiently far from the centre of the explosion, began to show signs of radiation sickness and was admitted to hospital. On August 3rd 1955 a number of paper cranes folded by well-wishers in Nagoya were sent to the hospital. Sadako began to fold her own cranes, symbolising her desire to get well. Sadako threaded the paper cranes she folded together into strings and hung them from the ceiling of her room in the hospital. By the end of August Sadako had folded 1,000 paper cranes, but she continued to fold more. Her condition continued to deteriorate and she died on October 25th 1955 having by then folded over 1300 paper cranes. Within three years of her death sufficient money had been raised to build a memorial to her in Hiroshima Peace Park. (Information from the website of the Hiroshima City virtual museum.) As a result of this, and a number of books and films about her, not all of which are very true to the facts, folding and stringing together a thousand paper cranes has become a common way to express a general desire for peace, or a more specific hope that nuclear weapons should never again be used. Many such strings are sent every year to the Hiroshima Peace Park to be displayed on or near Sadako's monument. Strings of a thousand paper cranes are also sometimes made as a more personal expression of good wishes for those who are unwell or dying. It is not altogether clear whether these various practices are a continuation of a pre-existing Japanese tradition or something completely new that has arisen as a result of the popularisation of Sadako Sasaki's story.

A paper crane folded by Sadako Sasaki from a sweet wrapper The earliest book to mention her, although only briefly, was 'Strahlen Aus Der Asche' written by the Austrian journalist Robert Jungk who had visited Hiroshima in 1956 and heard Sadako's story from a family friend called Kawamoto. He gives the number of paper cranes that Sadako folded as only 644 (p161 of the English translation entitled 'Children of the Ashes'). Another Austrian, Karl Bruckner, published the children's book 'Sadako Will Leben' in 1961. This book was translated into English as 'The Day of the Bomb'. It is a fictionalised and romanticised account of Sadako's life and death and gives the number of cranes she folded as 990. Another children's book, also giving a fictionalised and romanticised account, titled 'Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes' was published in 1977 by the Canadian born author Eleanor Coerr. Following Jungk, the number of cranes Sadako folded before her death is given as 644. ********* M: Paperfolding Organisations in Japan i. Master / pupil societies Akira Yoshizawa established his own origami society, called the International Origami Study Society, in 1954. At a much later date, probably in the 1960s, Toyoaki Kawai established his own society, called the Society for the Study of Creative Origami. Both these societies seem to have been based on the master / pupil relationship model of traditional Japanese arts and crafts education. ********** ii. The Sosaku Origami 67 Group In May 1967 a group of nine Japanese paperfolders, including Kunihiko Kasahara and Toshie Takahama, formed a new kind of origami society, one that was not led by an origami master but one in which all the members were equally free to make contributions and develop their talents in whatever way they saw fit. There is some confusion in the literature about how this group was formed. In his article about Kunihiko Kasahara, dated 22nd September, 2005, David Lister wrote: 'In 1965, Mrs.Toshie Takahama had visited New York for the World Fair as a member of a party led by Toyoaki Kawai. There Mrs Takahama met Lillian Oppenheimer and she was privately impressed by the way in which the Western folders of the Origami Center freely associated together on equal terms ... Toshie Takahama decided to form a similar sort of members’ society in Japan. In 1967, after one or two attempts that came to nothing, she helped to form “Sosaku Origami 67”'. On the other hand, according to Kunihiko Kasahara 'Around 1967, nine of us, origami enthusiasts, got together and almost spontaneously a group named “Creative Origami Group 67” was born.' (Source: Private email to Michael Naughton, translated by Nobuko Okabe) However it was formed, the group held exhibitions together, created origami props for a theatre production and models for TV advertising, and published a bi-annual magazine called 'Origami' in which designs by the members were published, including the famous module invented by Mitsunobu Sonobe. In 1970, they published a book, 'Atarashi Origami Nyumon' (Guide to New Origami), which, inter alia, contained some of the material previously published in the magazines. Thereafter the group seems to have ceased to function, perhaps because of the fornation of the more broadly based Japan Origami Creator's Association. ********** |

|||||||