| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 10/1/2026 x |

|||||||

| A Brief History of Educational and Recreational Paperfolding in Japan prior to Cross-Fertilisation (up to 1875) | |||||||

Introduction The history of Japan is conventionally divided into 'periods' as follows: Heian Period (794 -1192) Kamakura Period (1192-1333) Muromachi Period (1338-1573) Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573-1603) Edo Period (1603-1868) Meiji Period (1868-1912) Showa Period (1912-1945) It is commonly said that recreational paperfolding originated as far back as the Heian period, but as far as I know there is no evidence to back this assertion up. Almost all the early evidence dates from the Edo period. ********** A: Early References The earliest evidence for the existence of a recreational paperfolding tradition in Japan is this image of an Orizuru or Paper Cranes on a kosuka, which can, it is said, be reliably dated to 1591/3 (during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period)

There are two ways to account for the existence of such an accomplished representational paperfold at such an early date. The first possible theory is that the Paper Crane is not a one-off but that it is the sole survivor of a lost paperfolding culture which would also have included many other representational designs made in similar ways. This is an attractive idea, but the problem in believing it is that there is no evidence for the existence of any other similar designs at an early enough date. Surely some other design apart from the Paper Crane would have survived alongside it? The second possible theory is that the Paper Crane was a one-off design that was discovered by accident rather than created by design. A version of this theory was advanced by Isao Honda in his book 'The World of Origami':

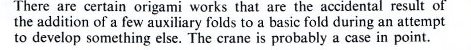

However, the idea that the accident happened 'during an attempt to develop something else' seems to take us straight back to theory one and I thus prefer the idea that the discovery might have happened entirely at random while some unknown ancient paperfolder was playing around with a square of paper. My version of the second theory has the merit that it does not necessitate imagining a whole lost culture of representational paperfolding design, but, of course, it is by its very nature unprovable. It is worth noting, however, that the idea of developing multiple designs from bases does not otherwise appear until the publication of the 'Orikata Tehon Chushingura' in 1797, and, even then, it is not the bird base that is used. ********** An early reference to what may be a recreational paperfold is found in a haiku in 'Saikaku Oyasawa' (Saikaku's Numerous Poems) by Iharu Saikaku, which was published in 1680. It reads 'Rosei-ga yume-no cho-wa orisue', which can be translated as 'The butterflies in Rosei's dream would be folded paper'. Unfortunately, we do not know what kind of folded paper butterfly the poet had in mind, and whether it was similar to the familiar Ocho and Mecho or something entirely different. ********** Koshoku Ichidai Otoko' ('The Life of an Amorous Man'), a novel by Iharu Saikaku published in 1682, refers to the hero, Yonosuke, making 'a pair of birds with folded paper' (identified as Hiyoku-no Tori - a pair of birds, one male and one female) and 'a pair of paper flowers attached to stems'. Unfortunately, the specific designs referred to cannot be identified. ********** B: The Classic Twelve Recreational paperfolding designs begin to appear in Hinagata Bon (kosode pattern books) and ukiyo-e prints (woodcut prints showing scenes of everyday life) in the early 18th century. The reason they appear at this date is probably not that they were not previously in existence, but that they were not previously recorded. Hinagata Bon and ukiyo-e prints both themselves appear at around this time. We probably only know of the Paper Crane from an earlier date because it was depicted on an artifact rather than in a print, and that artifact has chanced to survive. There are not many of these recreational designs, only nine if we exclude those practical designs which seem to have crossed over into the recreational paperfolding repertoire, the Basic Packet, the Thread Container, and the Collapsible Box, and only twelve if we include them (which I think we should). The various dates these twelve designs first appear are: The Paper Crane in 1591/3, the Basic Packet in 1648, the Takarabune (or Treasure Ship) in 1704, the Paper Boat in 1713, Komoso (a Buddhist monk) in 1705, the Thread Container in 1719, the Star-Shaped Box, the Sanbo on Legs, the Tamatebako (a modular cube) all in 1734, the Sanbo in 1735, the Collapsible Box in 1751, and the Inflatable Frog in 1752. Information about the Collapsible Box can be found in An Outline History of Practical, Religious, Ceremonial and Etiquettical Paperfolding in China, Japan and Western Europe. ********** After 1591/3, the Paper Crane does not appear in the historical record again until 1700, after a gap of over 100 years, when a design for a kosode (an early form of kimono) featuring Paper Cranes was published in the pattern book 'Tokiwa Hinagata' by Koheiji Terada and Shotaro Morida.

********** Thereafter Paper Cranes appear regularly in other woodcut prints. There are probably more prints featuring Paper Cranes than there are prints featuring all the other early representational designs added together. ********** The Takarabune (Treasure Ship) design (which is similar to, but not the same as, the Western European design known as the Chinese Junk) first appears in the kosode pattern book 'Tanzen Hiniigata, which was published in 1704.

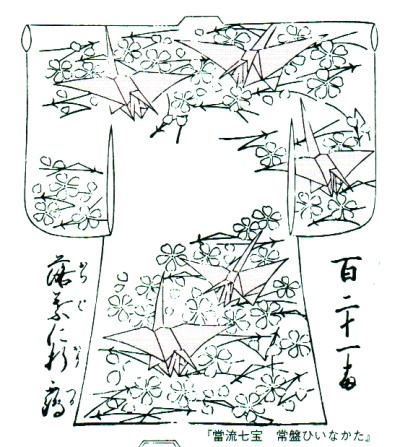

********** The Paper Boat with Three-Sails The print below is taken from 'Shotoku Hinagata' (aka Shotoku 3) by Nishikawa Sukenobu, a kosode pattern book which was published in 1713. It shows two types of model boat, one made largely of wood and the other a version of the Paper Boat. This is not the version folded from an oblong with which Western children are familiar but a similar design folded from a square which has two extra 45 degree points (perhaps intended to be interpreted as sails) in the centre of the boat.

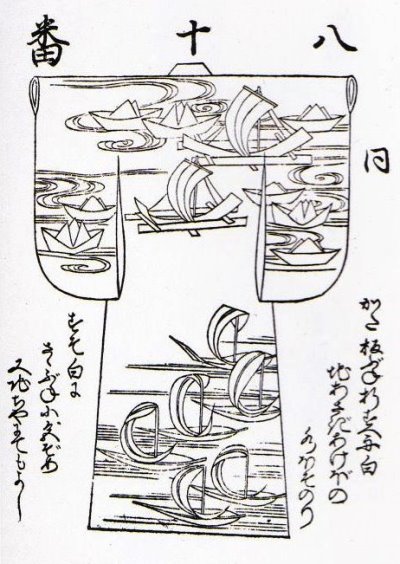

********** The Paper Boat with a Single Sail The 'Ranma Zushiki', which was published in Japan in 1734, contains a print showing a group of folded paper objects, among which are two Paper Boats. However, the version of the Paper Boat shown here is not the same as the Paper Boat with three sails that appears in earlier prints. This version lacks the extra central points and appears to have been folded from an oblong. It may thus be identical to the version we are familiar with in the West. It is not, however, possible to prove this similarity, since there are no published diagrams for any variant of the Paper Boat in Japan until relatively modern times. If it is the same as the European version, then we cannot completely discount the possibility that the single-sailed version of the Paper Boat may have been brought to Japan in the period between 1543 and 1639, when Western traders and missionaries were largely welcomed there (although there is no specific evidence to show that this occurred). Both the three-sailed and single-sailed versions of the Paper Boat continue to appear in the literature after 1734. However, Paper Boats with a single sail appear much more often after this date than Paper Boats with three sails do.

********** Prints showing folded paper representations of Komoso, a type of itinerant Buddhist monk who wore baskets over their heads, begin to appear in Japanese prints from 1705 onwards, though the form of the representations varies widely, and some look little like each other.

********** This image from the picture book 'Keisei Ori Tsuru', by an unknown author, which was published in 1717, shows a child being taught paperfolding in a terakoya (a school for the children of commoners). The detail shows the child writing a poem on the wing of one Paper Crane while another Paper Crane and a Komoso lie on the other end of the table.

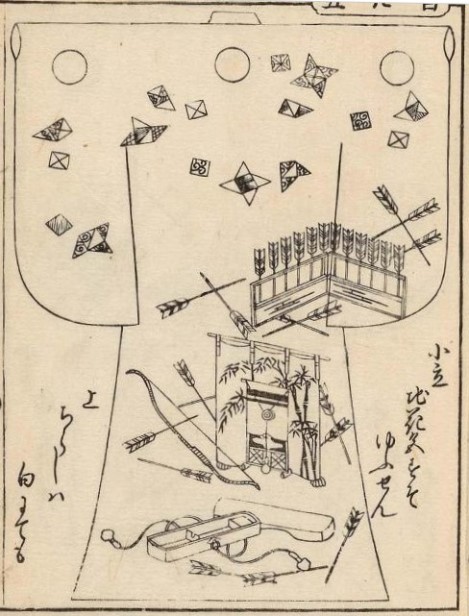

********** Komoso also appears in the 1734 print from the 'Ranma Zushiki'. ********** The earliest evidence for the existence of this design in Japan comes from a print in 'Hinagata kiku no nae', which is a kosode pattern book published in 1719. The author of the book is unknown. I do not know whether the conjunction of this design with archery in the pattern is significant or not. The Thread Container is the same design as the Western European design commonly called a Puzzle Purse. As far as I know the design was originated independently in both paperfolding traditions.

********** The Thread Container also appears in the 1734 print from the 'Ranma Zushiki'. ********** The Star-Shaped Box, the Sanbo on Legs and the Tamatebako The 1734 'Ranma Zushiki' print also contains illustrations of three other designs, the Star-Shaped Box, the Sanbo on Legs and the Tamatebako, all of which appear here for the first time. (The Star-Shaped Box is pictured from above in the bottom left corner, there are three different views of the Sanbo on Legs across the top, and two views of the Tamatebako (Treasure Chest).) (The design we nowadays call the Tamatebako is a cut modular cube made by combining six Thread Containers. However, there is nothing in the print itself to identify the specific modular method by which the cube would have been made, and, as far as I am aware, there are no other contemporary references that would help. There is therefore some small possibility that the cube pictured here is not in fact the cube we call the Tamatebako today.)

These three new designs could all be considered as practical paperfolds (two are boxes and the other can be used for storing small items) but from the context of the print it is clear that they are considered to belong to a single category, 'things you can fold from paper', and I therefore think it is fair to regard them as recreational paperfolds. ********** The Sanbo, first appears (lying on the floor at the front) in this print by Nishikawa Sukenobu which can be dated to 1735. The presence of other folded designs in this print, the Paper Crane and the Paper Boat, suggests that, although it is a container and therefore can be viewed as a practical design, it is, in this case, being folded for recreation rather than for practical use.

********** As far as I know the earliest appearance of the Inflatable Frog design is in this print, taken from the book 'Ehon hana no utage' by Nishikawa Suketada, which was published in 1752.

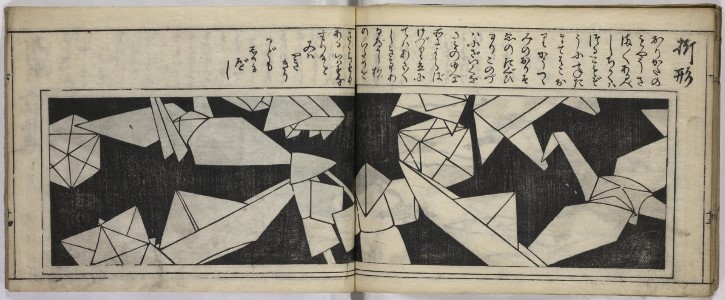

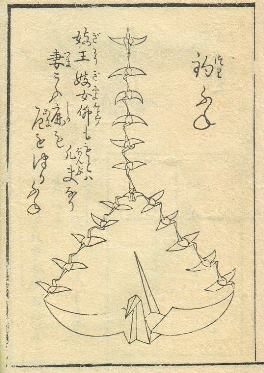

********** C: The Recreational Paperfolding Repertoire at 1752 The designs we have met to this point represent the whole of the repertoire of Japanese recreational paperfolds of which we have evidence up to 1752. It is difficult to believe that the 'Classic Twelve' could have been all the recreational paperfolds that existed prior to this date. They are surely the surviving remnants of a much greater repertoire of designs, most of which have not been recorded. Unfortunately, of course, there is no way of proving that this is true, unless further evidence is found, which, at this stage of the study of the subject, seems relatively unlikely. ********** D: Recreational Paperfolding after 1752 Many more recreational designs appear from the late 18th century onwards, although, unlike most of the earlier designs, many of these are achieved by using cuts or by starting from irregular paper shapes. Two publications from 1797 illustrate this type of development. The 'Senbazuru Orikata' shows how to fold connected Paper Cranes from large sheets slit into multiple sections, while the 'Orikata Tehon Chushingura' shows how to fold characters from the famous Japanese story called the Chushingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) starting from a heavily slit, star-shaped, paper shape. ********** 1797 saw the publication of the 'Senbazuru Orikata' (Folding a Thousand Cranes) in which the designs are created by first cutting slits in large squares to divide them into several, or many, smaller, but not completely separate, squares and then by folding each of these smaller squares into an Orizuru or Paper Crane. Because the squares are not entirely separated, the cranes remain connected by beak, legs, or wingtip when the design is complete.

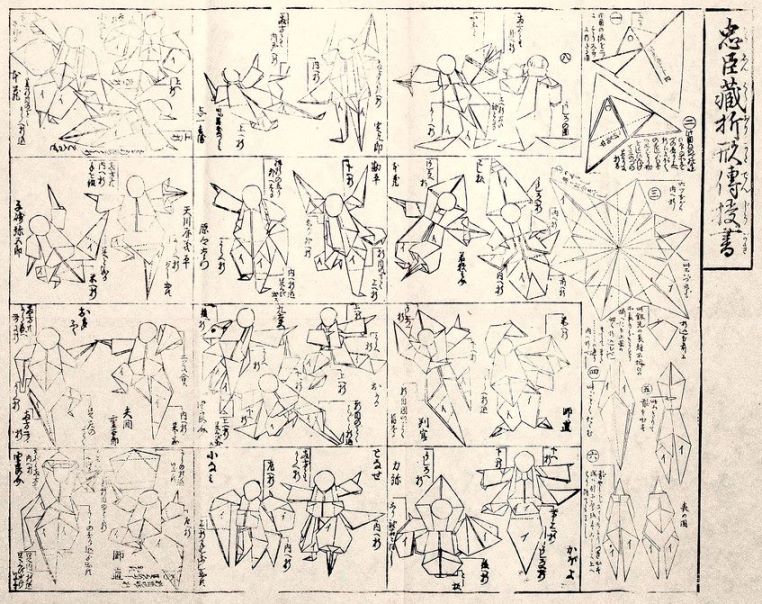

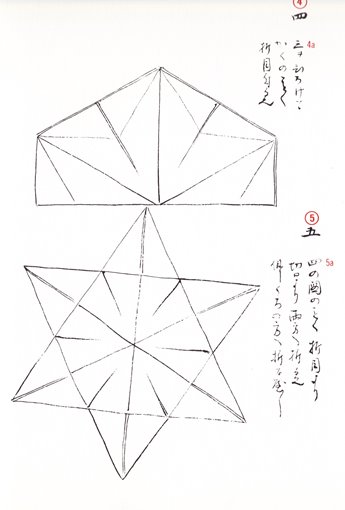

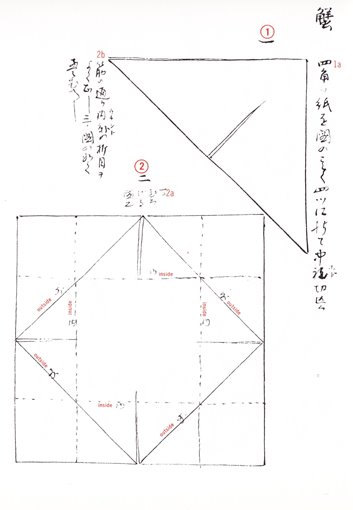

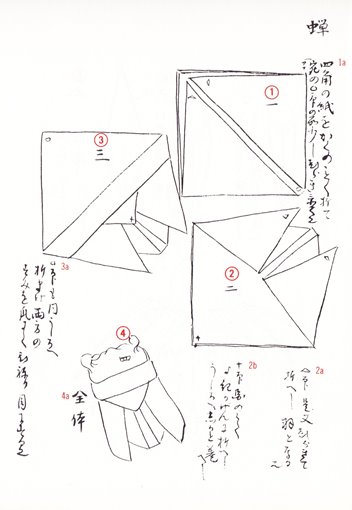

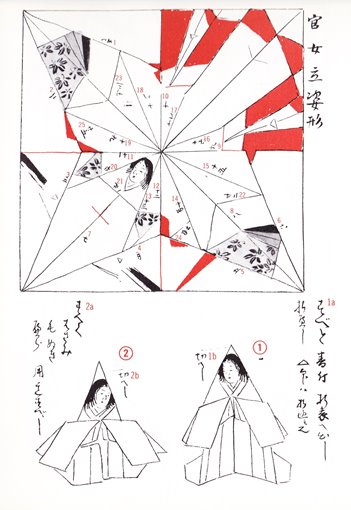

A page from the 'Senbazuru Orikata' showing a design known as 'Tethered Boats'. ********** Designs from Slit Bases The same year, 1797, also saw the publication of the 'Orikata Tehon Chushingura', a small leaflet which shows how to fold characters from the famous Japanese story called the Chushingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) in which the forty-seven ronin attempt to avenge the death of their master, Asano Naganori. All the figures are folded from the same base, which looks rather like a stretched Star of David into which slits have been cut to separate the six points. This, of course, means that it is easier to manipulate each point independently of the others.

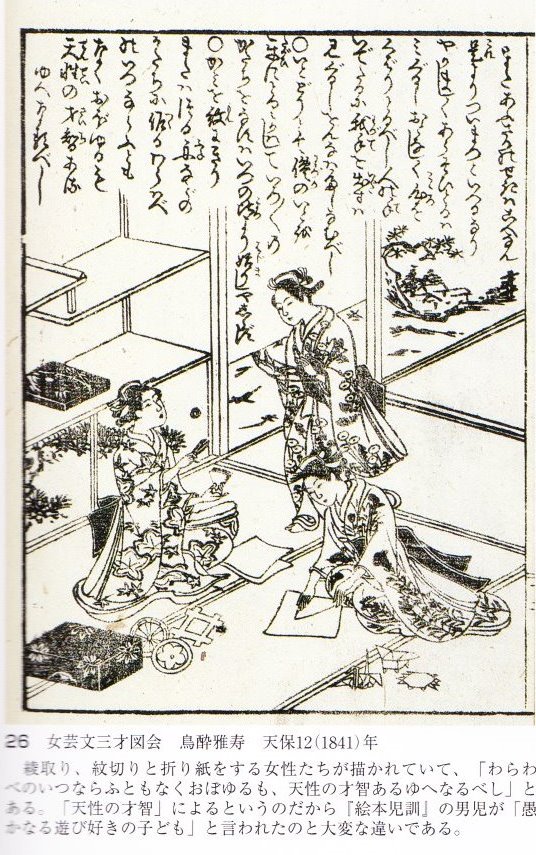

********** Fold and Cut Family Crests (Mon) This print, from 1841, provides evidence of another paperfolding related activity, in which the paper was first folded, then cut to produce the familiar symmetrical patterns of Japanese mon or family crests (lower right). The print also shows three folded designs, a Paper crane, a Sanbo on Legs and what appears to be a crab, which is probably a heavily cut design (lower left).

By 1845 it was possible for Katsuyuki Adachi to collect together diagrams for 48 varied paperfolding designs, including some of the classic etiquettical designs, but also others which seem to be purely recreational folds, and some of which are of substantial complexity, in a 63 page hand drawn ms that is commonly known as the Kan no mado. The Kan no mado (which roughly translates as Window on Midwinter)is a which is part of a much larger encyclopaedia known as the Kayaragusa. The Kan no mado ms was not publicly published until 1961 (see A Japanese Paper-Folding Classic) so that while it provides a useful record of the paperfolding designs known at the time it can have had little or no influence on the contemporary development of the craft. The vast majority of the designs are made from slit bases or non-convex paper shapes.

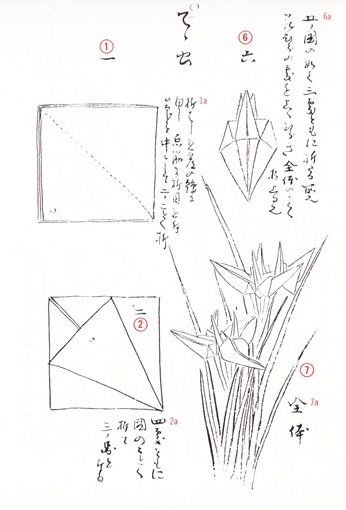

Just a few of the designs, the Cicada and the Iris (both of which appear here for the first time), the Snail, and the Blow-up Frog are made from single, unslit, convex shapes.

There are also instructions for folding eleven human figures from patterns painted onto squares (which are then slit to create the base the figure is folded from).

A note on page 24 states that 'Orikata is a favourite pastime for children and greatly enjoyed by them.' It then mentions other designs, the thousand cranes, boat, flowers, lotus, sambo, box, komoso, thread container and helmet, which are stated to be already well known and which are not therefore included in the ms (in order to spare the writer's brush.) Of this list, the helmet may be the Kabuto but the design of the flowers and the lotus are unknown. ********** The Simple Crane This design appears on a kimono in a print in vol 2 of 'Iro Shiki Shi', a book of shunga, by Insuitei Shozan (1821-1907). The book is undated, but thought to be from the mid 19th Century (see Iro shiki shi | Pulverer Collection).

********** The reference to a 'helmet' in the Kan no mado may well be a reference to the Kabuto. However, the first incontrovertible evidence for the existence of this design is this print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, dated c1854, which shows a woman holding a Kabuto out of reach of her child.

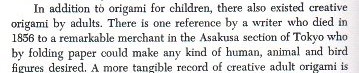

********** The Asakusa Merchant (prior to 1856) In the introductory material to James Minoru Sakoda's 'Modern Origami' there is mention of 'a remarkable merchant in the Asakusa section of Tokyo who by folding paper could make any kind of human, animal and bird figures required'. Unfortunately I have not been able to locate the reference in question, and this information must thus, at present, be regarded as unverified.

********** The man who would sit by the side of the road making origami There is a somewhat similar reference in the Preface to Isao Honda's 'All About Origami', which was published by Toto Bunka Company, Limited in Tokyo in 1960:.

As yet I have not been able to locate the source of this story. ********** E: The Japanese Recreational Paperfolding Repertoire at 1875 We have seen that there is evidence for a considerable widening of the recreational paperfolding repertoire beyond the Classic Twelve, although this appears to have been largely achieved by the use of slit bases, non-convex starting shapes and decoration. However, there is also evidence for the existence of a handful of (apparently) new designs made without using cuts, the Cicada, the Iris, the Snail, the Blow-up Frog, the Kabuto and, if the date assigned to the print above is correct, also the Simple Crane. ********** |

|||||||