| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 24/9/2024 x |

|||||||

| Marie de Guise's Paper Poulets | |||||||

This page attempts to collect information about the Paper Poulet, said to be a kind of folded love note which at some point during the folding (or unfolding) resembles the two wings of a chicken. The earliest known reference to a 'poulet' in this sense is from an uncomplementary popular song about Marie de Guise (later Queen of Scotland) which suggested that she 'loves paper poulets as much as (poulets) in fricasee' ('aimoit bien autant les poulets en papier qu'en fricasee)' (see entry for 1596). There is also a reference to a poulet, in the sense of a kind of love note, in Moliere's play 'L'Escole des maris' (see entry for 1661). In Furetiere's 'Dictionaire Universel', first published in 1690, he explains that this kind of love note was called a 'poulet' 'because in folding it two points were made which resembled the wings of a chicken' (parce qu'en le pliant on y faifoit deux pointes qui representoient led aisles d'un poulet). Unfortunately, no visual representations of such a 'poulet' are known. Indeed, all the representations we have of love notes from this period are rectangular, and of a much more conventionally folded kind. Assuming that Furetiere's description was correct, which is by no means certain, the only design I know of which could potentially be the 'poulet' design is the Square Letterfold. This does possess the necessary two points, which are folded inwards to lock the design into its final square form, and could, I suppose, with sufficient imagination, be seen as wings. The design is also possibly early enough, being evidenced from 1694 onwards. However, more evidence would be required, preferably in the form of an illustration accompanied by some identifying text, before we could be at all certain that this speculative identification was correct. Since both 'poulet' and 'cocotte' can mean chicken it is probably also necessary to consider whether this 'poulet' might be the now familiar Cocotte. To me this seems unlikely. There are two difficulties with the idea, first that the Cocotte paperfold is rather too complicated for a love note, and secondly that the mention from 1596 comes some 200+ years before the existence of the Cocotte is first evidenced. If the 'poulet' is the Cocotte then where has it been all that time and why is there no other evidence of its previous existence? There are several other, quite different, explanations of the origin of the name in the literature (see for example entries for 1831, 1856 and 1893 below). However, none of these alternatives seems sufficiently convincing that Furetiere's explanation must be immediately abandoned in their favour. ********** 1596 In Tome 2 of the 1827 version of the Duc de Sully's 'Memoires de Sully', originally published in 1638 as 'Les Economies Royale' and with a complex prior history of publication and revision, there is a passage which reads, the author putting words in the mouth of Henry VI of France, 'A l'egard de celles qui sont en France, vous avez ma neice de Guise, qui serait une de celles qui me plairaient le plus, malgre le petit bruit que quleques malins font courir, quelle aime bien autant les poulets en papiers qu'en fricasee'. (With regard to those who are in France, you have my neice de Guise, who would be one of those who would please me the most, despite the little noise that some clever people make, (that) she loves paper poulets as much as (poulets) in fricasee.) The footnote explains that 'what Henry says here about poulets, is from a song that was made against Mademoiselle de Guise which can be found in L'Etoile year 1596'.

Here is the same passage taken from a 1761 edition of an English translation.

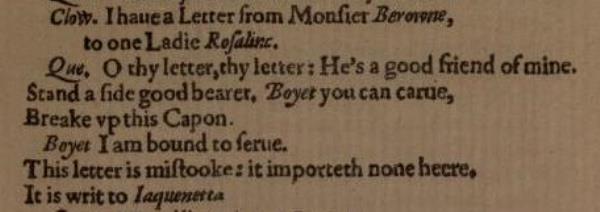

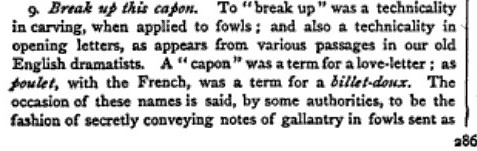

********** 1598 Mention of a 'capon' in the sense of a love letter occurs in Act 4 scene 1 of 'Love's Labour's Lost' by William Shakespeare, which was published in 1598.

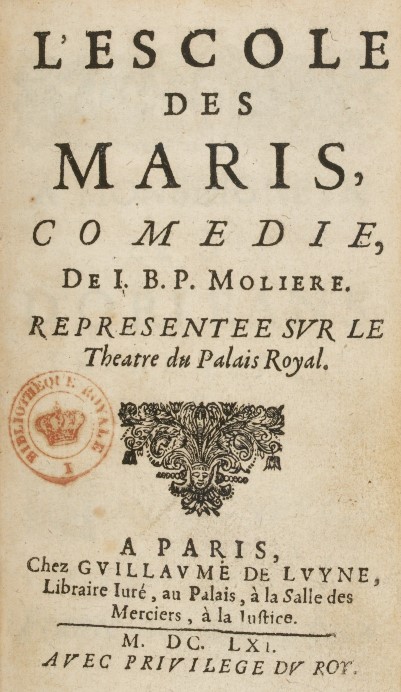

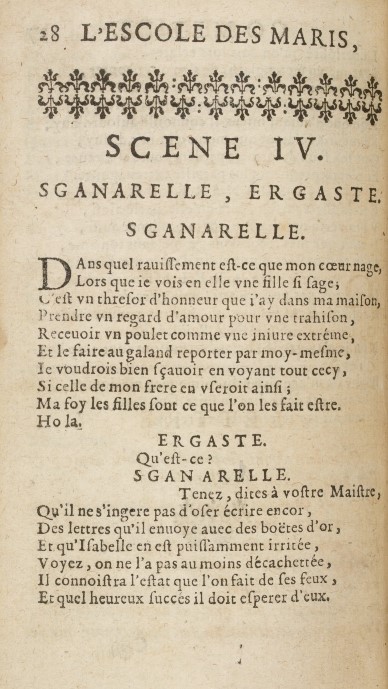

********** 1661 In Moliere's play 'L'Escole des maris', which was first performed and published in 1661, there is a line which reads 'Recevoir un poulet comme une injure extreme', which translates as 'To receive a chicken as an extreme insult'.

*** A footnote in the 1828 edition of Moliere's Complete Works explains that this 'poulet' is a 'billet amoureux, ainsi nomme, parce qu'en le pliant on y faisoit deaux pointes qui representoient les aisles d'un poulet', which translates as a 'love note, so named, because in folding it two points were made which resembled the wings of a chicken'.

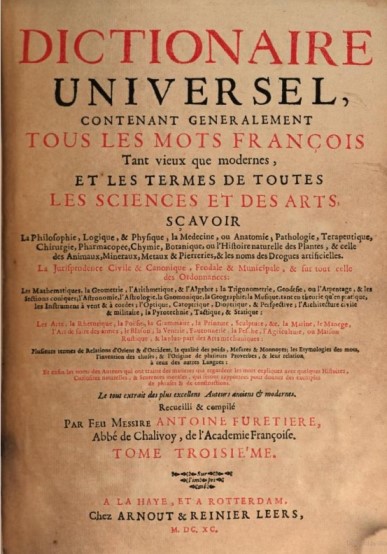

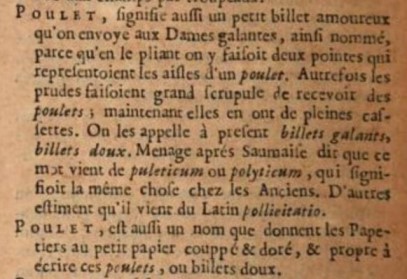

********** 1690 The information in this footnote appears to have been taken from Antoine Furetiere's 'Dictionaire Universel' published in 1690, which defines 'poulet', in this sense,as , 'aussi un petit billet amoureux qu'on envoye aux Dames galantes, ainsi nomme parce qu'en le pliant on y faifoit deux pointes qui representoient led aisles d'un poulet. Autrefois les prudes faisoient grand scruple de recevoir des poulets; maintenant elles en ont de pleines caffettes. On les appelles a present billet galants, billet doux. Menage apres Saumaise dit que ce mot vient de puleticum ou polyticum, qui signifioit la meme chose chez les Anciens. D'autres estiment qu'il vient du Latin pollicitatio.' Roughly translated, 'also a little love note which is sent to the gallant ladies, so named because in folding it two points were made which resembled the wings of a chicken. Formerly the prudes were very scrupulous about receiving poulets; now they have cupfuls of them. They are now called billet gallants, billet doux. Menage after Saumaise says that this word comes from puleticum or polyticum, which meant the same thing among the ancients. Others believe that it comes from the Latin pollicitatio.' ***

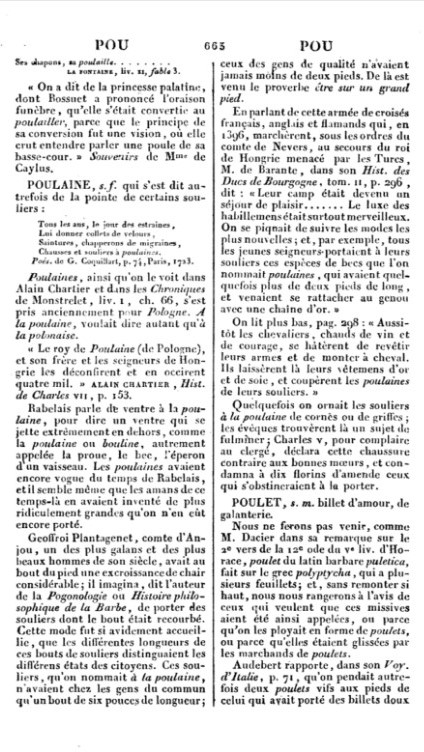

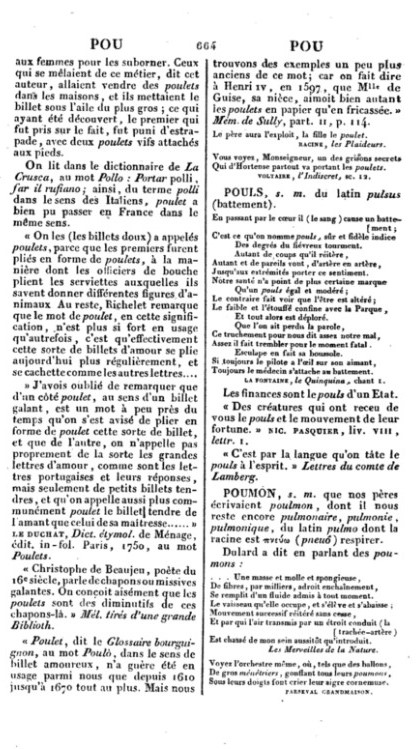

********** 1787 'Annotations ... upon Love's Labour's Lost' by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens et al, which was published in London in 1787, contains a section of commentary upon the mention of a 'capon' (ie a love letter) in Act 4 Scene 1 of this play. The usage of the term 'capon' here is said to be equivalent to the usage of the term 'poulet' in French and 'policella' in Italian. ********** 1831 In 'Philologie Francaise, by Noel and Carpentier, which was published in 1831, a possible alternative derivation of 'poulet' as the name for a love note is offered, 'parce qu'elles etaient glisees par les marchands de poulet' (because they were delivered by chicken sellers). However, the folding explanation is also offered and said to possibly be 'a la maniere dont les officiers de bouche plients les serviettes', which is unfortunately implausible due to the complexity of such folds.

********** 1856 (I have not translated this discussion of the origin of the term.)

********** c1878

********** 1893 (I have not translated this discussion of the origin of the term.)

********** 1894 There is a footnote in the 1894 'Oevres Completes ... de Branthome' which also mentions the Paper Poulet and Furetiere's definition. It says, very roughly paraphrased, 'Swallowing a poulet was not easy in those days when paper was neither thin nor easy to tear. The poulet then ran the alleys. The words made about her are the essence of her vogue, to quote only that of Henry IV saying of Miss de Guise that she 'loved chickens in paper as much as in fricassée'. Etymology is always controversial. I do not believe that poulet comes from the Italians, because this word is precisely missing from their language, at least with this meaning. Furetière must be closer to the truth by seeing in it an allusion to the folding of the love note in two, (making) points reminiscent of the wings of the chicken; they should compare this version with the popular expression 'faire des cocotes' which also designates a vague resemblance obtained by the folding of the paper. From chicken to cocote, there is not far.' The reference to 'swallowing a poulet' occurs on the previous page, which says, paraphrased very roughly, 'This great lady was surprised in her room by her husband, when she only came to receive a small paper poulet from her friend ... (she) was so well assisted by her soubz-dame (servant?) who took the poulet and swallowed it whole without tearing it in two, and without the husband noticing, who would have treated her badly if he had seen inside it. This was a great obligation of service which the great lady has always acknowledged.'

********** |

|||||||