| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 9/11/2024 x |

|||||||

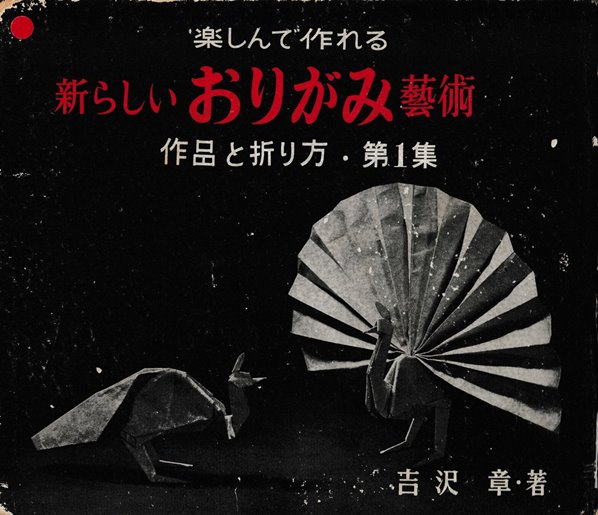

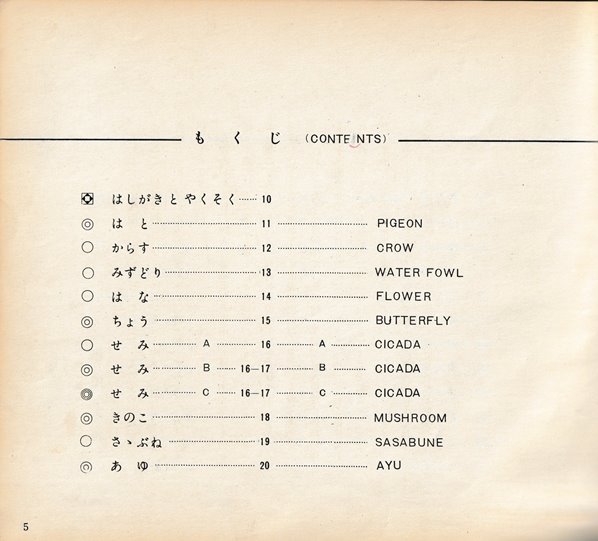

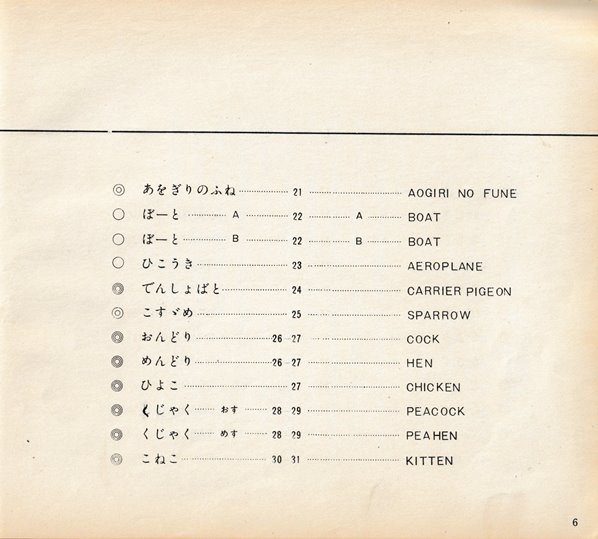

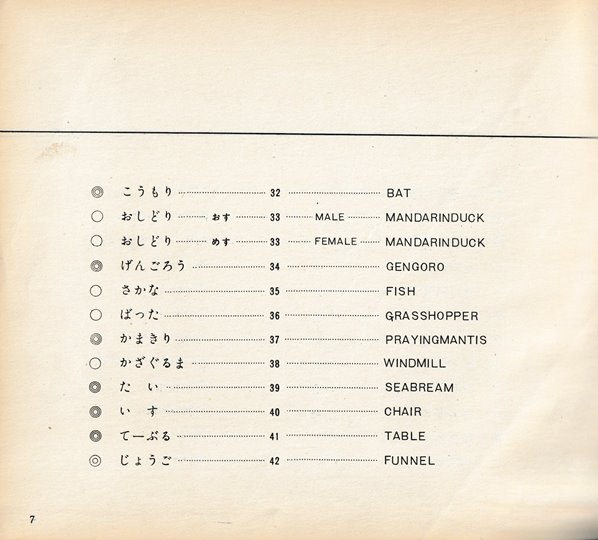

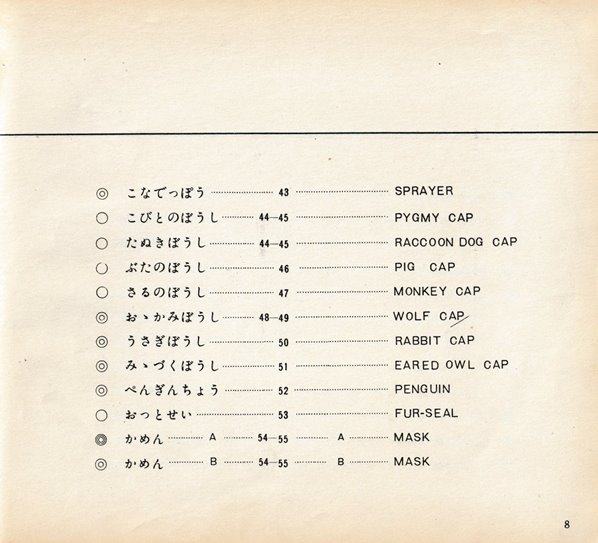

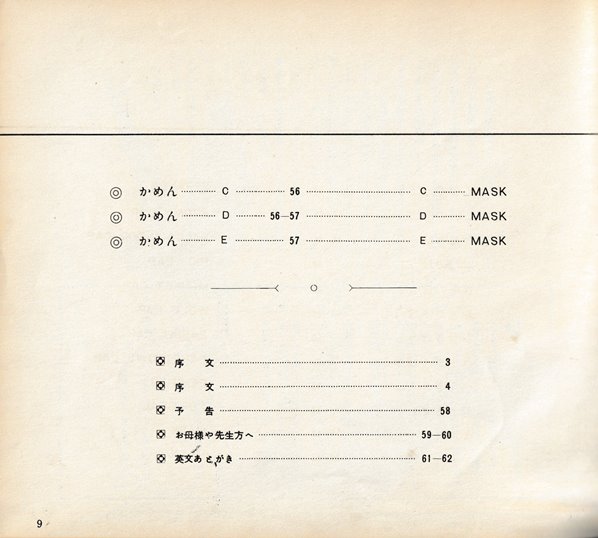

| Atari Origami Geijuitsu by Akira Yoshizawa, 1954 | |||||||

| 'Atari

Origami Geijuitsu' (New Origami Art) by Akira Yoshizawa

was published by Origami Geijutsu Sha (Origami Art

Publishers) on 1st April 1954, although the title page

states that it was printed on 25th December 1953. The

details on this page are taken from a copy of the work

dedicated to Robert Harbin by the author, which is now in

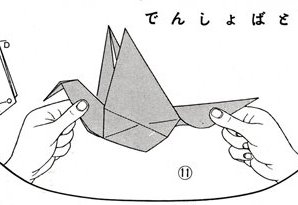

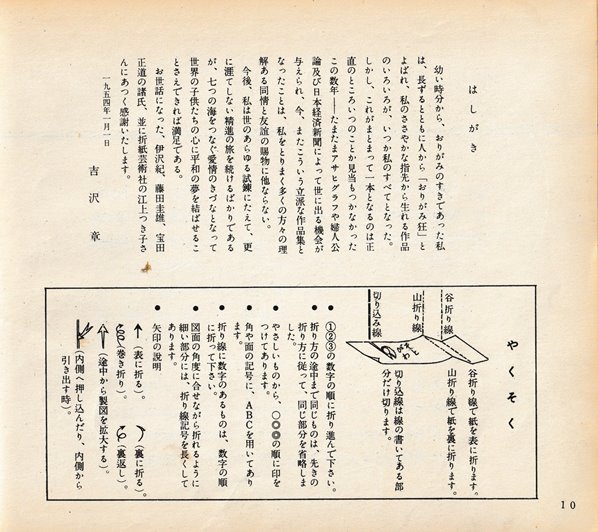

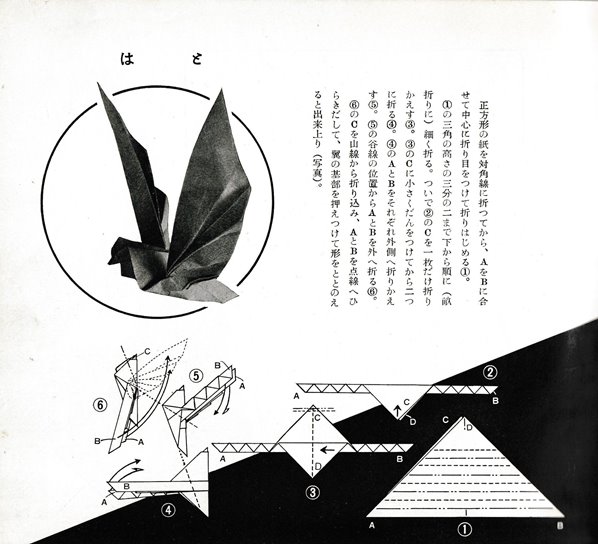

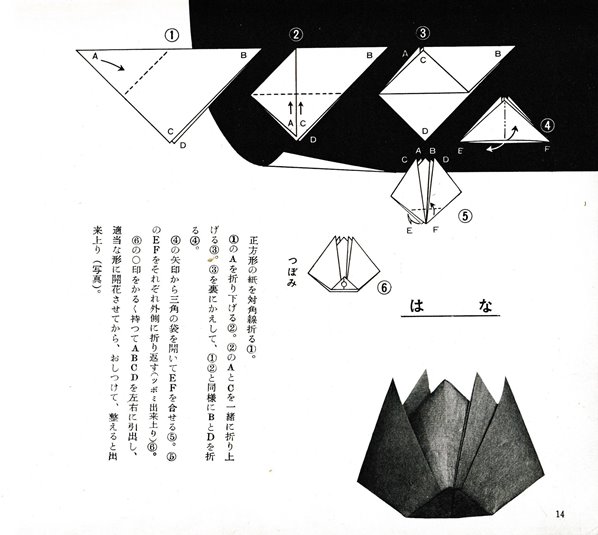

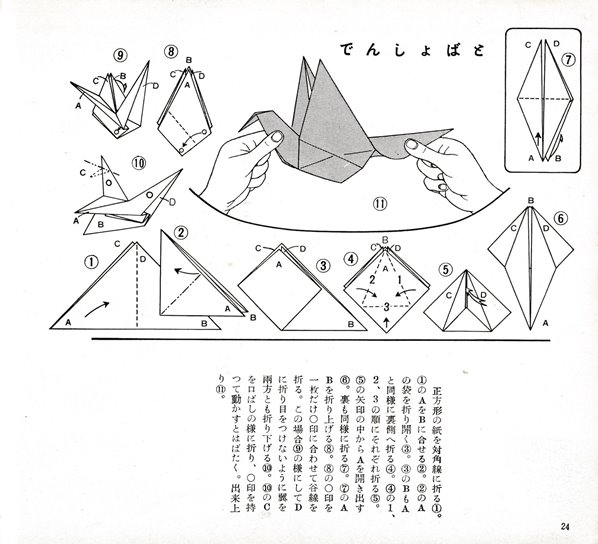

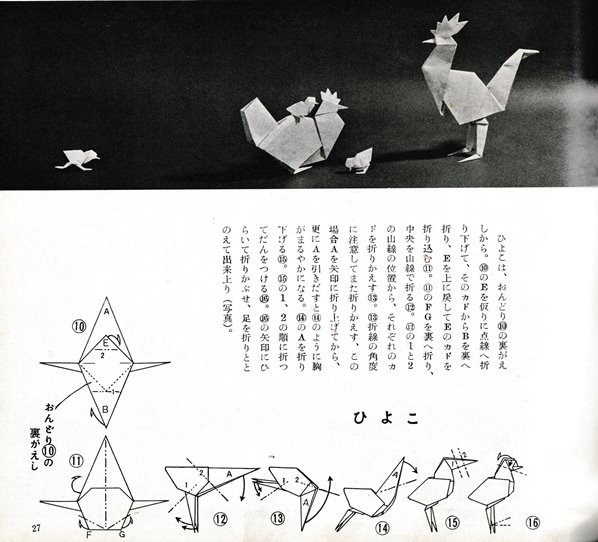

the library of the British Origami Society. ********** Introduction The original work consisted of two Forewords, a page explaining the diagramming system, various pages of diagrams and an author's Afterword. Yoshizawa subsequently wrote an additional Introduction in English. In David Lister's article 'The 1955 Exhibition By Akira Yoshizawa', written on 5th March 2005, he states 'The publishers later prepared some copies for Westerners and an additional introduction in English was stapled into the book.' To be clear, this English introduction was not stapled into existing finished books but added as an integral part of newly produced books when they were stapled together. I do not know at what date the English Introduction was added. In the article cited above David Lister states that 'The book was one of quite simple folding, but all the models were of Yoshizawa’s creation'. I cannot find any statement to this effect within the work and it is not clear to me whether or not it is completely true. The introductory material can be read in full below but I have extracted some of the passages which seem to me to be most important in illustrating Yoshizawa's views and intentions in publishing this work. ********** Inter alia, the English Introduction (see below) mentions that: 'It was more than 30 years ago that I first took up the art of 'paper folding' or Origami as it is known in Japan.' and 'Every day I create several new patterns of Origami.' 'Most of the origami patterns in this book have been selected for their simplicity.' 'All of them call for shuar (sic - ie square) sheets of paper.' (This is not precisely true. The diagrams on page 40 begin from a 3x1 rectangle.) 'I have avoided the use of scissors because I did not want my Origami works to transgress beyond the field of “paper folding”. The art of Origami should be differentiated from pure paper cutting. I did not color the patterns nor did draw lines on them, that is. I did not add eyes and noses on the face part of my patterns. All of such additional touches deprive the Origami art of its symbolic beauty.' (Note, however, that the crest of the Compound Peacock appears to be made using a cut. Also note that several of the designs are glued together, something that in Yoshizawa's view clearly does not deprive the designs of their symbolic beauty.) 'I am looking forward to seeing new patterns of Origami showing genuine subtlety created by those who take interest in and put value on the art of Origami.' ********** Inter alia, the First Foreword (see below), written by Tadasu Iizawa, the Editor of the Asahi Graf newspaper (which had first published some of Yoshizawa's designs), says, roughly translated: 'Yoshizawa-san is truly a genuine person. He is about to turn 50, but he still does origami. Some people call him eccentric, but when you talk to him, you realize he is just a focussed person and not strange at all. At present, he doesn't have a particular job and makes a living from origami, so it seems that his life is pretty tough, but he says, "If it comes down to it, I'll just start selling tsukudani again." Since I'm the one who introduced him to the world of journalism, I feel a strong sense of responsibility, but there are already researchers from outside Japan who have come to learn from him, so I am very pleased that his art will be further recognised with this new book. His works already number in the thousands, and even if I pose a difficult challenge, the next time we meet he has already folded it. It is amazing! These days he is even trying to make a leap from sketching nature to the world of abstraction.' ********** Inter alia, the Second Foreword (see below), written by Keio Fujita, the Editor in Chief of Chuokoron (the parent company of Fujin Korin magazine, which had also published articles explaining Yoshizawa's designs), says, roughly translated: 'I went to kindergarten for three years and had many female friends, so I knew a lot about origami ... One day, Takada Masamichi of the Fujin Koron editorial department brought in something strange. Calling it strange is a bit of a misnomer. It was a piece of origami that was extremely well made. It was a beautiful piece that could only be described as art, unlike our handicrafts. It was Yoshizawa's work, and for the next year he contributed various pieces to Fujin Koron.' ********** Inter alia, the Author's Afterword (see below) says, roughly translated: 'Records show that the tradition has a history of more than a thousand years, and some origami was used for recreational purposes, others for ceremonial purposes, and others for religious purposes. For a long time, there were creations that correctly conveyed the life of origami, and on the other hand, there were things like paper crafts that led origami down a wrong path, but when it went out of fashion, it was only the old folding methods that were passed down from generation to generation, and it was unfortunate that nothing new was created, for various reasons. However, fortunately, our "creative origami" has recently been generally accepted, which is very gratifying.' 'One thing I would like to mention is the friendship I have with Professor G. Legman of New York. He is an enthusiastic researcher of origami, which is rare for a foreigner, and as I have exchanged opinions with him about the history of origami, I have come to feel more confident about the spread of origami around the world. In a recent letter, he, who is now in Paris, encouraged me to translate and publish my book in English, French, and Spanish, and also to launch a world peace movement through origami as one of the projects of UNESCO and the International Red Cross.' ********** Analysis At present this is only a selective, not a full, analysis of the designs in the work. Flapping Bird This design has similarities to The Flapping Bird, but it is developed from the bird base in a different way and, as far as I can see, the flapping mechanism is not as good.

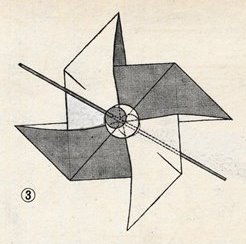

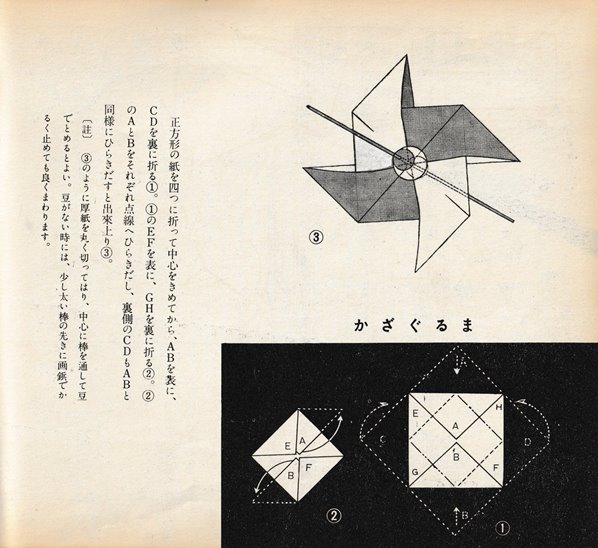

********** The Bicolour Windmill

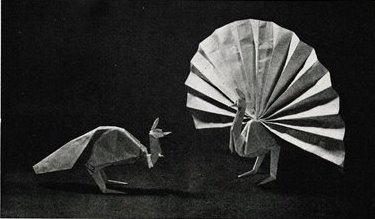

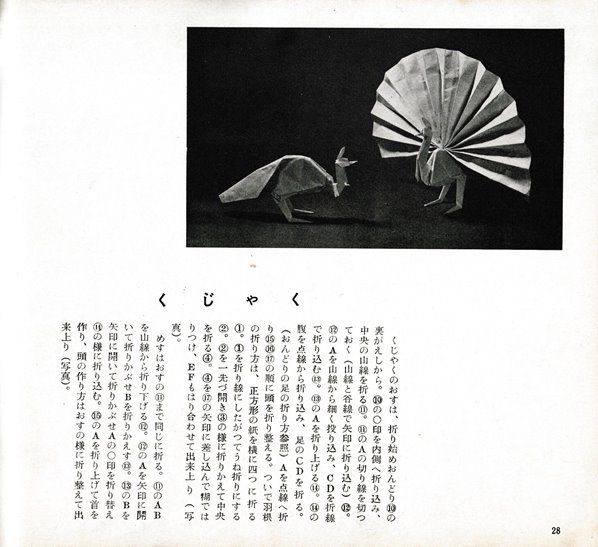

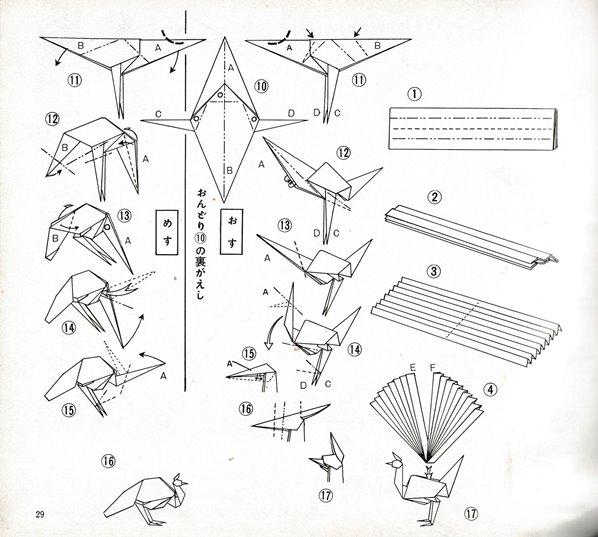

********** The Compound Peacock (Honda's Peacock) Note that in this version of the Compound Peacock design the tail is glued inside rather than outside the body. It appears to me that the crest is created by means of a cut.

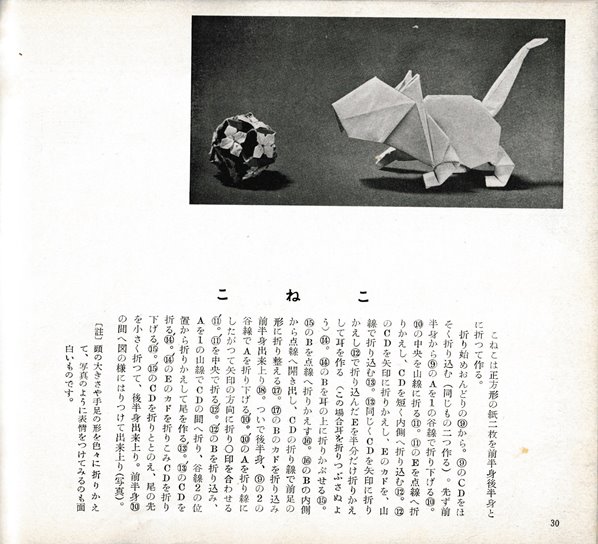

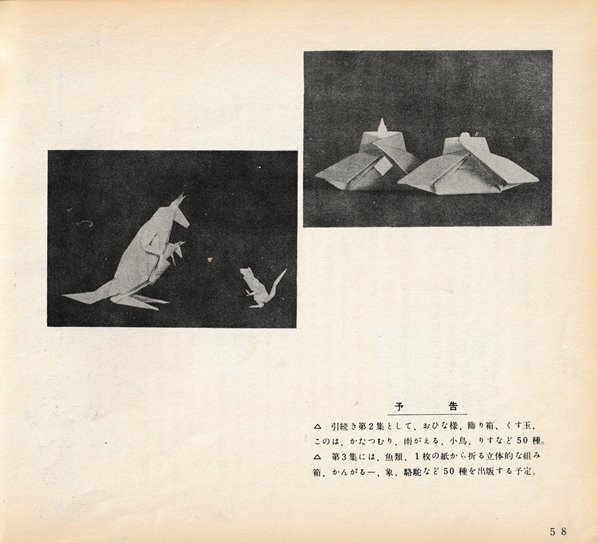

********** Kusudama This design appears in a photograph but is not diagrammed or mentioned in the text. It is not clear whether it is a glued multi-piece or a modular origami design.

********** The Work

********** English Introduction

********** Japanese Forewords

**********

********** Author's Afterword

********** The Work

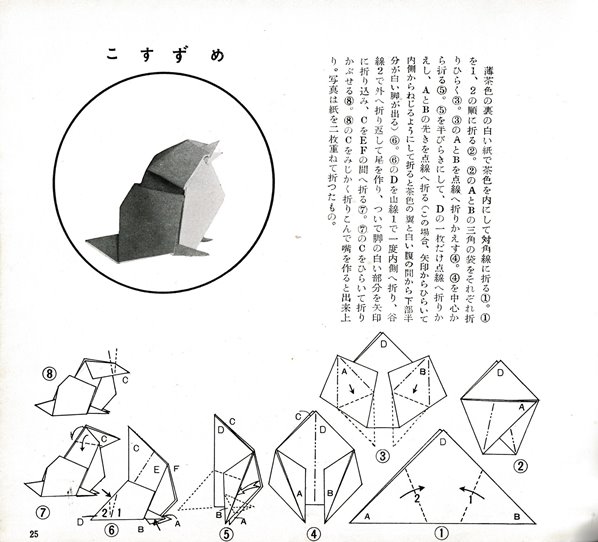

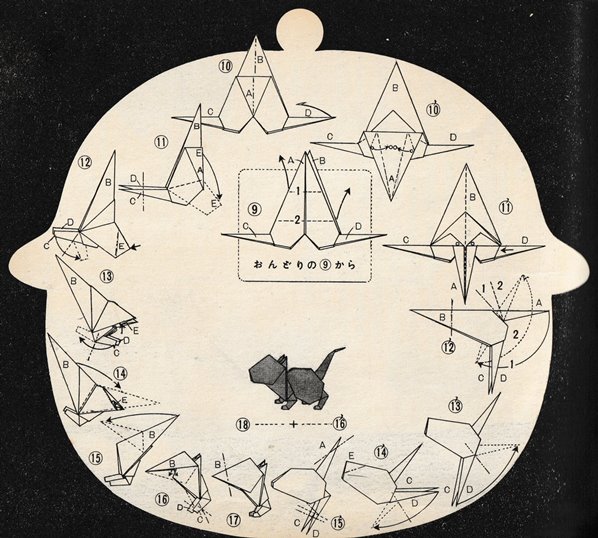

Note that the Kitten is a glued compound design.

********** |

|||||||